EARLY OCTOBER 2022

THE CHILDREN LAUGH and move in buoyant, colorful streams. They parade through the hotel lobby out into the bright morning smog, jostling and bouncing off one another. They wear Mickey Mouse ears and giddy grins of anticipation. They lead a line of parents pushing baby strollers past stuffed animals and cartoon backpacks. They fill the sidewalks, heading toward the happiest place children know.

They are heading to Disneyland.

The doctor walks against the tide of happy children, moving through the lobby toward the convention center. The children pass around him, and as their laughter fades into the street, the doctor finds himself floating among the business attired. They amble toward the arena, the 2022 meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. They wear blue and white badges. Many carry poster tubes of research.

They gather around the arena now, where the speakers are about to begin their keynotes. The doctor makes his way to the backstage entrance. He will be the last to speak.

He is honored to speak here, and yet he would rather be anyplace else. He does not feel like the hero some say he is, and he reminds those who ask: He did not save anyone that day. There are some people, he knows, who do not want him to be here, giving these speeches. They want only the parents to speak. There are rumors, whispered to him in his small pediatric clinic back home. Rumors that some parents think him selfish. That when he gave the other speeches, a testimony before Congress, an introduction on the White House lawn before the president, he was doing it for himself. For fame.

It is absurd, he thinks. Who would ask for such a job? Who would find profit in remembering over and over again such a horrible thing?

Every time he gives a version of this speech, it is as if he is rewinding the horrible tape of his memory. He always begins with “the Before,” when there were no murals painted on the walls downtown, no crosses in the town square. The cemetery grounds remain unbroken. The children’s cries are now smiles as they stream backward into school. The shell casings lift from the classroom floors. Miah arrives at his office for her morning appointment, but he has not yet told her she can go back. Back to Robb Elementary.

He waits for his cue.

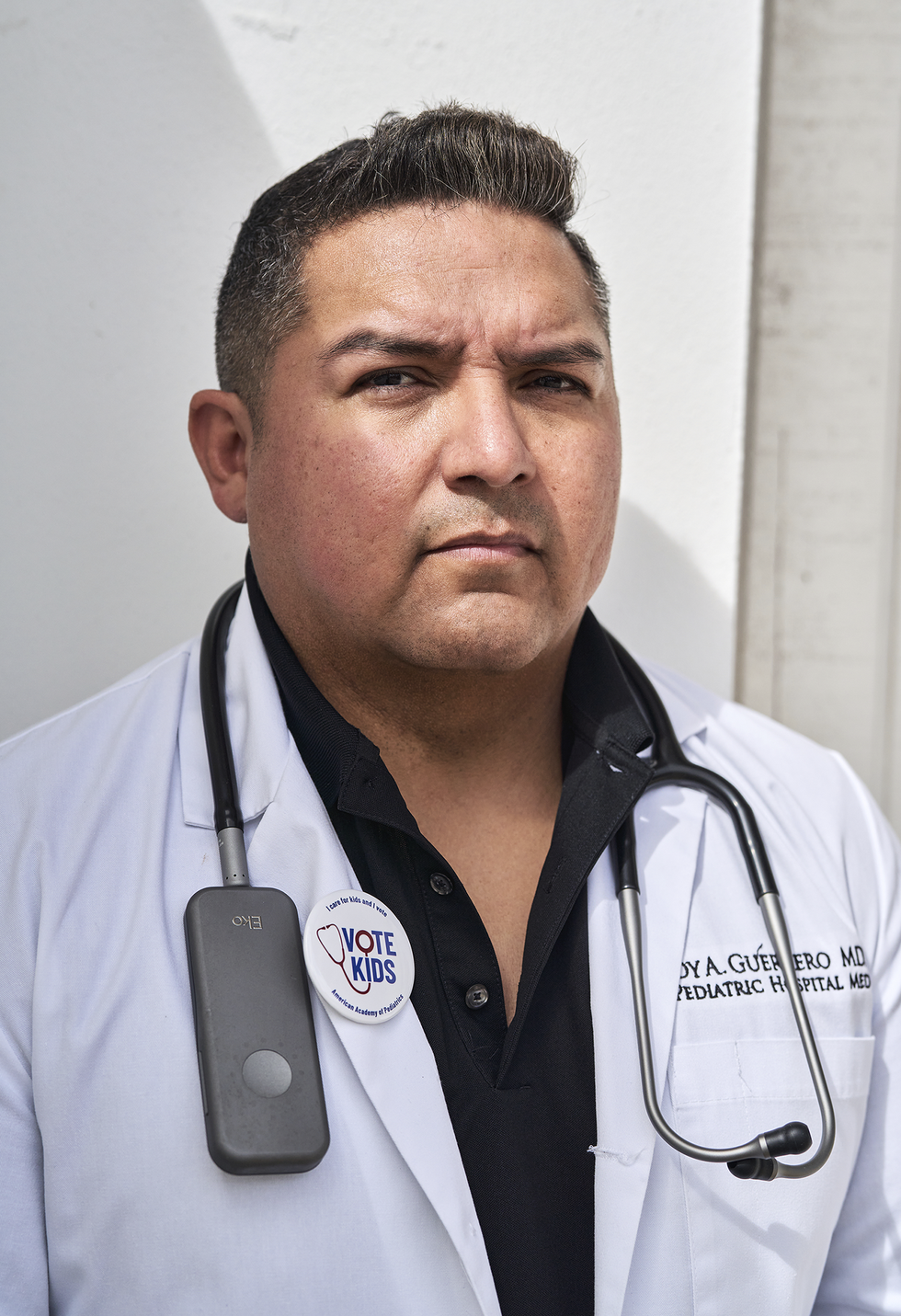

The executive vice president of the AAP: “It is my unbelievable honor to introduce you to Dr. Roy Guerrero.”

The thousand or so pediatricians in the convention hall rise to their feet and applaud. Guerrero walks onto the stage, wearing black slacks and a dark pinstripe blazer over a bright-white shirt, open at the collar. He has a lumberjack’s barrel chest, a buzz cut, and kind eyes. He smiles the warm, tired smile he gives before he tells the story no one is ever ready to hear.

He begins, showing photos of his town before the murals and the crosses and the graves. He introduces his clinic, the only pediatric clinic in Uvalde, Texas, where he is the town’s only pediatrician.

Then, drawing a deep breath, he says, “I don’t know if there’s any children in the audience right now. It’d be a good time to step out if you don’t want your child to hear this.” He says he’s going to play an audio clip from the school that day, a clip that has never been played publicly—not when he testified before Congress, not when he met with President Biden or with the police or the Border Patrol. He says the clip is the voices of children being pulled to safety; the killing happened in classrooms across the hall.

The girl whose voice they will hear most prominently, he says, survived. Her mother gave him permission to play this clip now. She felt it was essential to play it. He says it again: “So, if anyone wants to step out now, please do so.” He starts the tape.

The arena fills with the static screech of a girl’s almost unintelligible screams. A long treble of helpless, terrified cries, the chilling pleas of a child.

“The police, the police, the police! The police are here!”

A FEW DAYS EARLIER

TIME REWINDS. The doctor leaves Uvalde. East on I-90. Past roadside bars and spidery industrial machinery and abandoned gas stations and cattle ranches and mile-long freight trains. A billboard shouts a message he supports: “Vote Beto!” There’s a picture of Robb Elementary School juxtaposed with a quote from Governor Greg Abbott: “It could have been worse.”

Guerrero drives with his husband, Jose, who is a nurse at the clinic. They will drive to San Antonio, where they will catch a flight to Anaheim for Roy’s speech. As he leaves Uvalde’s city limits, he feels stacks of weight slough off his shoulders. To leave Uvalde is to breathe again.

Of the heavy fragments of memory that day, what weighs on him most now are the faces of the parents who were screaming to him, pleading for his help. He cannot get their cries out of his head. He remembers the word. Seen over and over again that day. In text conversations. Posted on social media into the night.

Missing.

“My son is missing.”

“Still missing.”

He saw their children. He knew that night they were not missing. These days he often sees the parents of the dead children he saw at the hospital that day. At events. At the meetings. Uvalde Strong for Child Safety, the group he helped found. Every time he sees them, there is a lump in his throat. He wants to tell them what he saw, what it meant, but he can’t. He’s not ready.

“No one knows how to deal with this, even myself, after the fact, after what I saw,” he says. “I don’t know how to deal with this, man. I don’t know what I’m supposed to feel or not feel.”

In his clinic, he hears rumors. Parents talk about other parents—who is and who is not allowed to hurt, not allowed to be angry, not allowed to take action. He sees the town divided now into four groups: parents of children who died, parents of children who were injured, parents of children who were there but did not die or get injured, and everyone else. He is not sure where he belongs. He explains how some in the town categorize him: “You don’t have a kid that was injured or that was related to you, so you don’t know how I feel.”

There is confusion and hurt in his eyes as he recounts this. “No, it’s the opposite,” he says, pleading. “You don’t know how I feel. I had five kids that I’d seen since they were newborns that passed away. How dare you, on your side, say that you know how I feel, too? Because you don’t.”

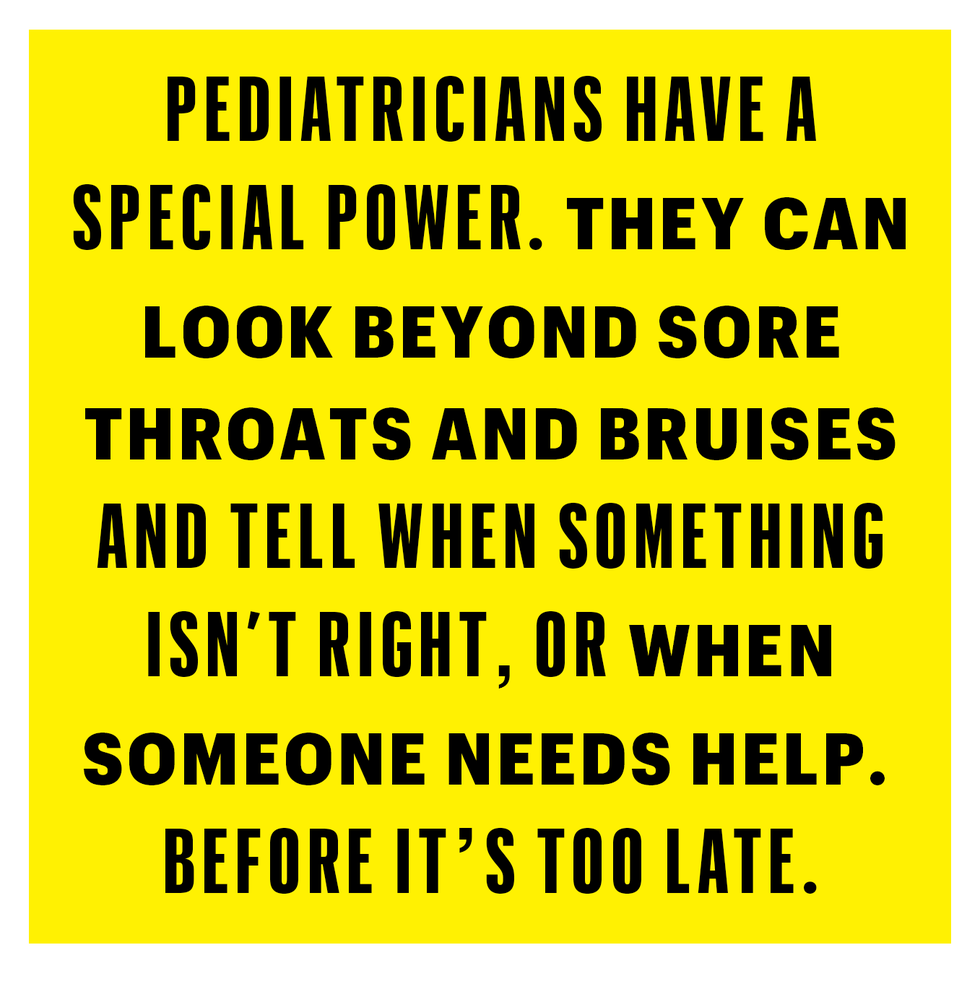

He is 44. He does not have children of his own, but when asked he tells others he has 4,000. He sees almost 40 a day. He cannot protect them all. He knows this. Every pediatrician knows tragedy. Disease and car accidents are always possible. But they are comprehensible. The death of five of his patients one morning is not. They were in class and then they vanished. And with them vanished years of clinic visits and vaccinations and tongues stuck out, years of care, his life’s work. He chose pediatrics because children, he thinks, make for the best patients. They are less resistant to change. Adults, he finds, are resistant. He is no exception. When you devote yourself to the care of children, wrapping ankle sprains and peering into eyes and ears and throats, charting their growing heights and weights each checkup, and when they keep returning, year after year, the illusion builds: You can protect them. You have a special power, and that power is keeping them safe. In how many other professions can one’s illusion of purpose vanish so suddenly? Where else can you feel as if you have failed so completely?

He passes outside the city limits and once again his neck begins to relax, the knots loosen.

The town has always felt like a high school to him. Rumors and gossip and resentment. He recently had to remind his nurses that wherever they go, people are watching. The nurses had been at a bar, and someone saw them and posted something about it on social media. He even had to cancel the Día de los Muertos parade because there was too much infighting. Parent A not wanting Parent B there. Parents A and B not wanting the police there. Parent C wanting the police there.

Welcome to Uvalde, he tells you if you look surprised at such things.

A DAY BEFORE THAT

IT IS A SMALL TOWN. So small it appears suddenly, like a motel sign, like a coyote across the road.

It is a drive-through town, a stop along a roaring I-90, which slices through west Texas and slows only for the blink-blink of yellow traffic lights and the apparition of other towns, their names announced on water towers dotting a blue expanse. The road to Uvalde bumps past these towers, past ranches and rusted rail tracks and brown farmland, where San Antonio’s English radio stations begin to crackle with static and where men and women stand roadside on Sunday, holding small signs. Jesus heals and forgives. The town appears suddenly along this road, and then suddenly it is gone. It is roughly five miles long. From the barbecue-joint-and-gun-shop in the east, where the town gathers for lunch, to the Fairplex on the western edge, where the town hosts rodeos, where state troopers rendezvous with National Guard soldiers for border exercises, and over which the sun sets blood orange each night. The road gets dark, and then Uvalde fades in the mirror.

Roy Guerrero’s clinic is on the eastern side, just a mile up the road from Uvalde Memorial Hospital and just a mile down the road from the barbecue-joint-and-gun-shop and one of the elementary schools. The children’s parents drive them here, through the gates to a small one-story stucco compound—clay roof tiles, a little chimney, painted car tires piled here and there, a concrete wall along the perimeter that fences in an overgrown side yard where tractors lie in various states of rust, as if being pulled into the earth. The sun beats down. It is usually quiet, save for the sharp buzzing of crickets in the surrounding weeds and the distant whoosh of cars on I-90, speeding to other towns. He lives here—through the door in the back is the home he shares with his aging father and Jose.

It is October now. Neighborhood kids wait to cruise on bicycles after the bell, riding past election signs and 12-foot ghosts and witches in front yards. It is Tuesday. The doctor sits at his desk, scrolling through patient names, his afternoon schedule. Late-morning sunlight glows through the translucent window above his workspace. It is not so much an office as a large cubby, low walls surrounding a desk and computer and binders and reminders pinned to the wall, so small one might mistake it for an open-floor storage closet and so close to the front desk he can chat with his nurses without turning from his screen.

He is from Uvalde. He ranched and rode horses as a kid and went tubing in the rivers north of the city. He still meets friends from grade school in town, at the hospital where he first opened his practice in 2010. His kids call him Dr. G.

Dr. G calls from his desk to a nursing student.

“Are you in 2, or you finished 2 already?”

“I’m done with 2,” she calls back.

A child is waiting in exam room 2. He redesigned the clinic during the pandemic: Each of the five exam rooms has a door leading to the courtyard so patients can enter without encountering others. In the courtyard, Dr. G has set up 21 chairs, each with a name, representing the 19 children and two teachers who were shot to death at Robb Elementary. His kiddos pass the chairs on their way in. They pass a banner with the same message seen everywhere in town these days. uvalde strong. When they check in at the desk, they see two signs. protect our kids not guns!! one reads. And the other: 05. 24. 22.

His office protocol includes a new question, which the nurses ask the children in the exam rooms. “Were you at Robb that day? Were you affected, directly, indirectly?” Almost everybody says yes.

The doctor bounces up from his swivel chair, brushing past his small office wall and into exam room 2.

“Say ahhh. Aghhhhh!”

He’s looking forward to leaving town. He can feel the tension building in his neck, like knots. He saw a therapist after it all happened. Everyone still asks him, “How are you doing?” He tells them he’s fine. “I know myself,” he says. “I’m very objective. It happened. There’s nothing that I can do about it. To change it. It is what it is.”

He and Jose live part-time in San Antonio now. They have a Med Spa there. Acne treatments and laser hair removal and lip fillers and other procedures. They dine out, they have a drink without worry of judgment or gossip. They dance and hike and attend concerts and travel to resorts far from Texas.

When he is here in Uvalde, he is devoted to this town. But it feels like work. He doesn’t really go to the bars, the restaurants, the rodeos, the football games anymore. Uvalde will always be home. But home is no longer a place he can stay for long.

SEPTEMBER

THE START OF SCHOOL in Uvalde loomed all summer like a mandatory sentence.

All summer the kids came into the clinic and said they did not want to go back to school. They were afraid someone was coming for them. All summer he told them, No one is coming for you. You are safe. But of course he could not be sure this was true. There were some kiddos for whom nothing worked to assuage the paranoia; in a small town, everything is a trigger. He recommended to some parents that they consider not sending their children back. Some kids are taking online courses.

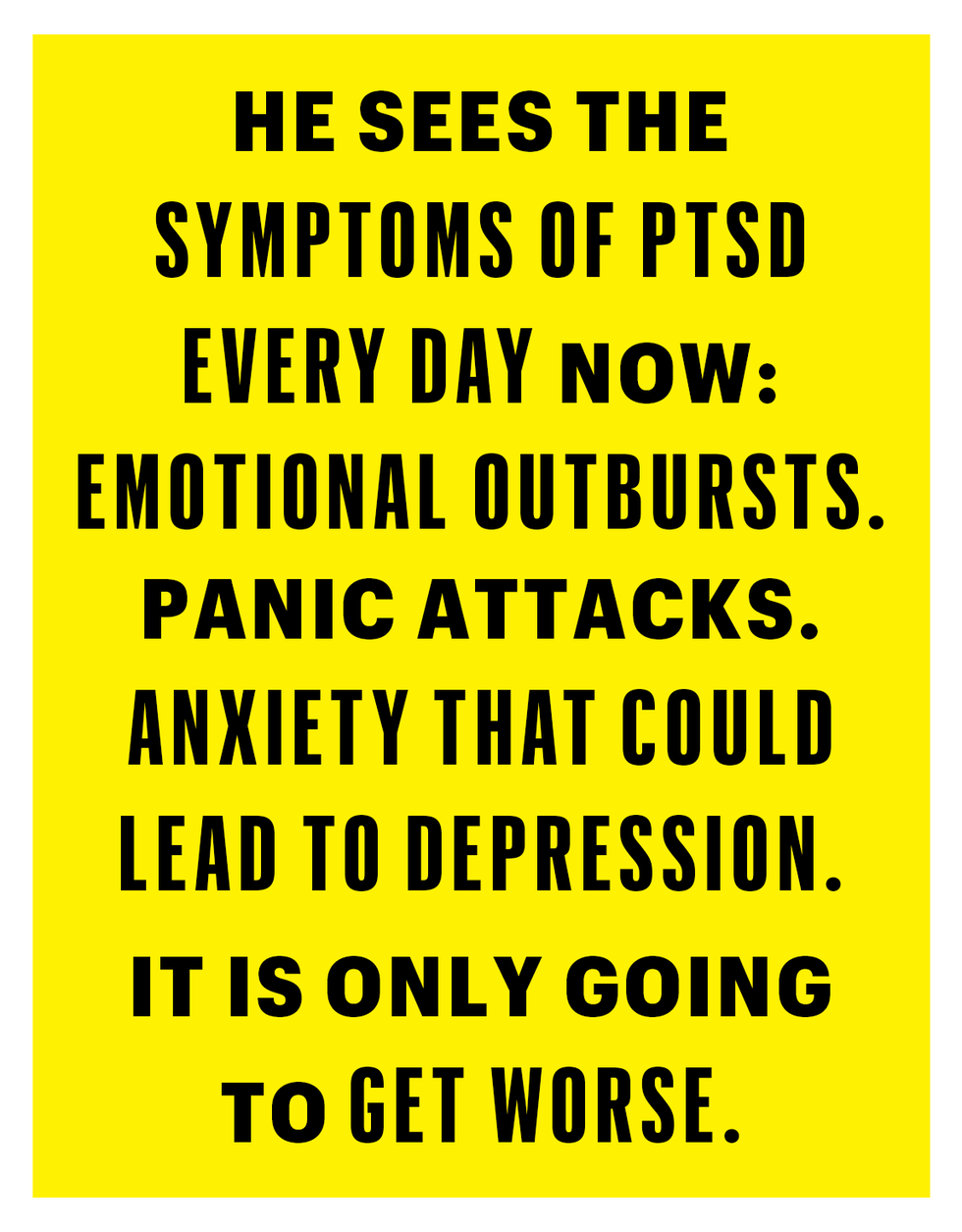

Many of the children who go to school that first week appear in his office almost immediately. Their symptoms are all the same. They have stomachaches and headaches and chest pain and heart palpitations. They are not constipated. There is no organic explanation. They have stomach pain every morning before school, and the cause is clear. Until recently, he was not able to diagnose PTSD; the shooting was too recent. But he sees the symptoms. Every day, he treats at least six kids with these symptoms. Emotional outbursts. Panic attacks. Anxiety that could lead to depression. It is only going to get worse. He used to be so happy-go-lucky, parents tell him. Now he’s clingy and never wants to leave our side. Some play and then suddenly stare blankly—at the floor, at the sky. Some are having delusions; he doesn’t know what else to call them. They see things out of the corner of their eye, through the window at school, at home. They think it’s the shooter coming back for them.

We can’t leave her alone, their parents tell him.

Or, There can’t be loud noises. He can’t see different people he hasn’t seen before.

The children are trying to forget. But their bodies remember.

In the flatlands of west Texas, one must leave town to forget. In Uvalde, there is a new, grim routine to the everyday.

Drive to the town center. See the empty fountain painted sky blue and lined with pale crosses. On them, see the handwriting of adults and the handwriting of other children. happy birthday i miss you. See the flowers beneath, the teddy bears, a bag of ramen noodles, a Converse sneaker, the souvenirs one accumulates in a life of just 11 years. See the laminated pictures pinned to the trunks of trees in the square. A girl holding an honor-roll certificate. There is a picture on every tree, and still there are not enough trees and so some children share. A school bus passes the green. Then another school bus. The children on the bus sit at the light and, looking out to their right, watch the trees and crosses of their dead schoolmates. See the murals nearby in an alley where a stray cat ambles under hot scaffolding and where the school bus passes next. Their painted faces are reflected in shop windows over sweaters and cowboy hats and jewelry and ceramics and morning shoppers. Drive by the schools at the afternoon bell. See the lines of cars waiting for pickup, the parents parked side by side, the ones who do not want their kids riding buses. See the large black fences looming over the playground, the teachers calling now, “Girls, hurry, we’re about to go in!” Pass a large black state-trooper car. And another. And another. And another. They patrol the town. Around the schools during pickup. Up and down I-90. Drive down that strip when the sun sets. Try to escape, have dinner in peace. Drive to the Mexican restaurant, where the town gathers on Sunday nights. Iced tea is served in large Styrofoam cups, and old men in boots hobble up to the counter to pay. Above the bar, the Beto campaign commercial has just come on. The one with the parents holding photos of their dead children. A man with a warm gap-toothed smile watches blankly beside a woman and three bottles of Bud Light and two Budweisers, watches as his neighbors tell him what their child wanted to be when they grew up but will never be. On the street outside in the night, see all the signs, the flags, the bumper stickers, the shirts, the writing on shop windows. uvalde strong. uvalde strong. uvalde strong. The neon sign outside the furniture store, the words glowing through the night along I-90 as you make your quiet drive to bed.

Every day is like this. The doctor wants to remember. He wants other adults to remember. For them, remembering is strength and, he hopes, change. But he also wants his kiddos to forget. For them, forgetting is medicine. It is grace. He doesn’t know how they can cope in a space so small, so full of what has been lost.

JULY

TWO MONTHS AFTER the shooting, Roy Guerrero visits his mother’s grave.

Hillcrest Cemetery lies on the town’s western edge, over the Leona River, just before the fairgrounds. It is a mile or two down the road from the center of town, where for weeks that spring families prayed in churches over the bodies of their children and then followed their caskets, under crisscross power lines, past small one-story homes and the crowing of vagabond roosters, to the cemetery. The last child, Layla Salazar, was buried here. In a casket of white and sunflower yellow and blue, amid several mounds of dirt still fresh and covering 15 of her classmates and two of her teachers.

As Roy looks around his mother’s grave, he sees the small mounds of dark-brown dirt. He hopes they are not what he thinks, but when he walks near, he can see. They are the children. He goes from grave to grave. He looks over the bouquets of flowers, the pinwheels, the items placed below the temporary crosses, the gravestones not yet here. There is a teddy bear and a baseball cap and a stuffed unicorn and a doll and a small Eiffel Tower and a T-Rex and many other memories piled in the form of toys.

As the summer progressed, the rumors sprouted. That Dr. Guerrero can’t know what they, the parents, feel. He is not a parent himself. He should not be giving speeches. Only the parents should speak. He does not understand their loss.

He was working in Del Rio, a larger town 70 miles west on I-90, near the Mexican border, when his mom got sick. He was working as a medical director there. The pay was bundles more than what he made owning his own practice in Uvalde, but he wasn’t happy in Del Rio. He stayed there for two years. Then his mother had a stroke. So he came home.

He had missed Uvalde. He remembers warmth; he remembers joy. He remembers taking the school bus from the family ranch where he was born and raised with goats and rattlesnakes. He remembers the fenceless fields by the school, the long brick building. He remembers running through its halls to visit friends and the smell of hamburgers in the cafeteria on Thursdays and Mr. Aguilera, one of the best teachers he ever had, because he was so kind and because he wanted nothing but the best for Roy. He remembers being quiet. Shy. He remembers always looking forward to the next day at Robb Elementary. His school.

She died eight months before the shooting. He feels his mother inside his house now. He feels her with him, guiding him. He believes she brought him home for a reason. She had always wanted him to return, to stay, to care for the community. It is as if she knew in her heart what was about to happen.

MAY 24, 2022

IT IS TUESDAY. The office takes the usual calls, parents asking after coughs and sports physicals. In the morning, Miah comes. The pediatrician has known her since she was a baby; she survived liver surgeries then, against all odds.

She walks from the gravel parking lot over a stone path, under an archway, and through the courtyard into the exam room. Dr. Roy Guerrero comes in soon to see her. She is wearing a white Lilo & Stitch T-shirt.

Miah says she left school this morning with a small cough. Dr. G takes a look—“Aghhhhhhh”—and tells her it’s nothing serious.

There is something in his mannerisms, his speech, the quick grin he will give, that seems childlike, something warm and curious and attentive to everything at once. He likes to talk. His voice is soft and clear and rises with exuberance when he greets his kids.

Miah says she wants to go back to school. There are only a couple days left before summer vacation. Her younger sister, Elena, is at school now. And so Dr. G lets her go. And Miah leaves.

She goes back to Robb.

The office closes at lunchtime. They drive to Oasis Outback, a barbecue joint just down the road, off the town’s main strip. It is a community place. It sells barbecue smokers and firepits out front and children’s jeans and lunch boxes at the entrance. The restaurant inside is mess-hall style, a wood-paneled cafeteria of sorts with buck and bull heads mounted on the wood walls and where everyone—local crews and out-of-town workers and state troopers and neighbors—gathers for brisket and bottled Coke. Past the restaurant in the back is one of the town’s gun shops, where an assault rifle was purchased two days ago, just 50 steps from where the pediatrician and his nurses now sit.

The doctor is eating his lunch when he gets the text. It’s from a buddy in San Antonio, a trauma surgeon. “Hey Guerrero,” it begins, what everyone calls him. “Why is every single trauma surgeon and PD anesthesiologist on call for a mass shooting in Uvalde?” Guerrero doesn’t understand the text. When he, Jose, and the nurses leave the restaurant, there are helicopters buzzing overhead, police cruisers screaming west down the strip.

He calls a nurse at Uvalde Memorial Hospital to find out if they need him to come.

“Yes, get over here right now.”

It is pandemonium. Outside the ER on his way to the entrance, he passes the federal agents and police and Border Patrol and a wall of parents. The parents are sobbing. They are screaming the names of children. They begin yelling at him, too. Go, look, find our children! One is the mother of Miah and Elena.

Inside there are kids along the hallways bleeding and screaming. Nurses and doctors dart between curtained rooms. He walks by four or five children in the hallway with minor injuries. He turns to another adult: “All these kids are from my office . . . .” It had been a routine morning just an hour ago.

“Hey, Dr. G!”

It is Miah. She is sitting in the hallway. Her face is placid, unmoving. Her body shakes. Her white Lilo & Stitch shirt is covered in blood, and she has a shrapnel wound in her shoulder.

“Miah . . . I just saw you.”

“I know,” she says. “I went back to school.” She tells him what she saw. She was in the room where it happened. Her classmates were falling over. They were bleeding. Her best friend, lying next to her, was bleeding badly. Their teacher was throwing up blood. She slid her phone to Miah so the girl could call 911. Miah smeared her best friend’s blood onto her own hands, then rubbed it on herself and lay still, so it would look like she was dead. She waited. She didn’t move until it was over.

Miah is 11.

Outside, Guerrero tells Miah’s mother: He found her. She is okay.

Her mother replies, her voice shaking with a disorienting mix of gratitude and fear:

“Where is Elena?”

He rushes back inside, as if in a fever dream, back down the hallway of the ER to the exam rooms where children, their injuries worse, are being tended to. In each room there is another grotesque tableau. A man, unrelated to the shooting, appears to be having a heart attack. Guerrero sees another of his kids behind a curtain, Noah.

The boy’s shoulder is blown out, and Guerrero can see the open flesh. Two doctors are working on the boy. A bullet had penetrated his shoulder blade from behind, opening a ten-inch gash before punching shrapnel out through the front. Guerrero has never seen such an injury. He has never before treated a gunshot wound.

He searches every room. Every hallway. He cannot find Elena. A nurse tells him that there are two children in the back, moved to the surgical area.

“Two dead children,” she says.

He asks to go see the children. A different nurse leads him there.

The worst he had ever seen in this small town was a dog mauling. A two-year-old was attacked by a pitbull down the road from his clinic. He saw the child here at this hospital. He had come to identify the body. The child’s neck had been ripped open. He could see everything inside.

What he sees now in the surgical area is even worse.

The two small bodies before him now have been pulverized. One of the children has a chest wound so large he is sure it would have killed a grown man. He looks at the child’s face. It is not Elena, a fact that provides no comfort. The other body has been decapitated. The flesh around the child’s neck is torn.

He will not know the child’s identity until later that night, when he sees the photos on the news and recognizes the cartoon shirt and cartoon shoes. For now, he knows by the clothes it is not Elena, and looking away from the bodies, he still has hope that others can be saved.

When he returns to the hall, a nurse asks him to station himself in the ER lobby. There are 14 patients on the way, he is told. Several ambulances. Nurses tell him to be ready to help triage. He waits with other doctors and nurses and first responders and hospital staff. Everyone has gathered. They wait the first hour. They wait the second hour. He is praying that the children will come. If they come here, it means they have a chance. He is standing beside a speech pathologist from the hospital. He has known her since they were in kindergarten. He sees her here all the time. While they are waiting, she gets a call. She answers and then breaks down sobbing. Her friend Eva Mireles, one of the two teachers in the classroom with Miah, has died.

He knows now. The other children are not coming.

The messages begin to arrive from parents on social media, all with that hopeful word. Missing. He knows the children are not missing. Later, the news identifies the dead. He begins to recognize the names. None are Elena. She is okay. But there are five from his office. One was on his schedule for that afternoon. A kid he has known since they were a baby. They had an appointment at his clinic. That afternoon.

The pediatrician wants to tell the parents of the two children what he saw, what the injuries mean. Still, he is unable to utter the words, the grim reassurance.

Your child did not suffer.

They were killed instantly.

They never stood a chance.

EARLY OCTOBER 2022

THE THOUSAND PEDIATRICIANS in the convention hall rise to their feet and applaud as Guerrero takes the stage.

He is honored to speak here, and yet he would rather be anyplace else. He does not feel like the hero some say he is, and he reminds those who ask: He did not save anyone that day. He never had the chance.

Jose sits in front—a woman leans over and rubs his shoulder.

The doctor begins.

“I want to break this talk into three different parts,” he says. “The Before, the During, and the After.” One of the first slides he shows on a large screen is from Before, a photo of himself surrounded by seven of his patients. “Me and some of my kiddos,” he says. “This was actually taken about three weeks before the shooting happened.”

And then he plays the audio clip, and the girl’s screams cut through the convention center. It is important that the audience hears. That they relive this terrible memory with him.

Dr. G doesn’t talk about the police response, and while he makes a few comments about gun control, he is a doctor. He talks mostly about his responsibility—their collective responsibility—as doctors. It is not said, but all in the room understand: A physician’s responsibility has become something grotesque. They see battlefield injuries now. Blowouts. Penetrating wounds that sever limbs and explode faces. To treat these wounds, Guerrero believes they must vote. The cause of such wounds is clear. He urges people to vote for a candidate who will protect the well-being “of our children.” But the pediatrician’s role in the community, he notes, in the medical care of its children, is not just dressings over a wound. It is a constant looking after. And so he helps refer kids to therapists. And checks in on them, all children.

He pauses.

“Now, there is one dark thing I want to talk about,” he says.

The shooter.

“The AAP’s motto is ‘Dedicated to the health of all children,’ ” he says. “This shooter, a few months before, was a child. Correct? . . . I’m not trying to defend or excuse anything that the shooter did that day, but there was a systematic failure in our community, and our schools, and as medical professionals, that possibly could have averted this disaster if it was reported accordingly. . . . Why didn’t anyone report that this kiddo was slashing his face at school and then showing it off to people, saying that it looked cool?”

Doctors, he says—pediatricians—have a special power. It’s not to protect children from everything. Rather, their power lies in the trust families place in them. Pediatricians can see things about children; they can sense things about families. They can look beyond the white spots in the back of the throat or the soccer bruise, and they can tell when something isn’t right. When someone needs help. And they can try to help before it’s too late.

A few days before, he had sat in his makeshift cubby-office at the clinic, thinking about the speech—what he would say and, perhaps, why he was giving it at all. “I can at least fight to make things right or at least attempt to, even if I fail,” he said, leaning forward in his worn chair, eyebrows up. “You just can’t sit back and do nothing. Especially after what I saw.”

After the speech, the pediatricians stand and applaud, and then they begin filing out prematurely, before the hosts, their eyes swollen and red, can return to the mic. Some doctors stay outside the entrance to shake his hand, to thank him. And then it is only him and Jose outside the doors. They will fly back to San Antonio this afternoon, then drive the almost two hours to Uvalde. Dr. G has a full schedule of kiddos tomorrow, starting first thing.

A version of this story appears in the Jan/Feb 2023 issue of Men's Health.