IT'S A COOL late-summer afternoon in Telluride, Colorado. Jagged Rocky Mountain peaks frame a blue sky, and the buzz in the air owes as much to the 8,750-foot elevation as to the lanyard-wearing cinephiles swarming the ski town’s world-renowned film festival—the flannel shirt of Hollywood junkets. About 12 hours earlier, the audience at the Chuck Jones Cinema gave a standing ovation to Sterling K. Brown and his costars after the premiere of a new movie called Waves, and no sooner did the applause die down than people picked it (and Brown) as grade-A awards bait.

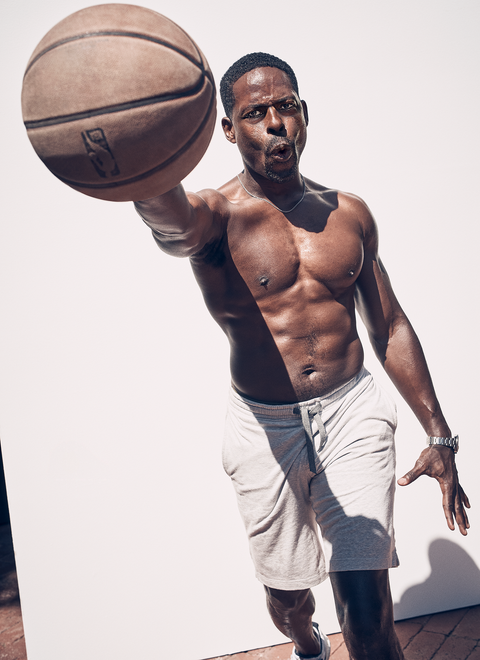

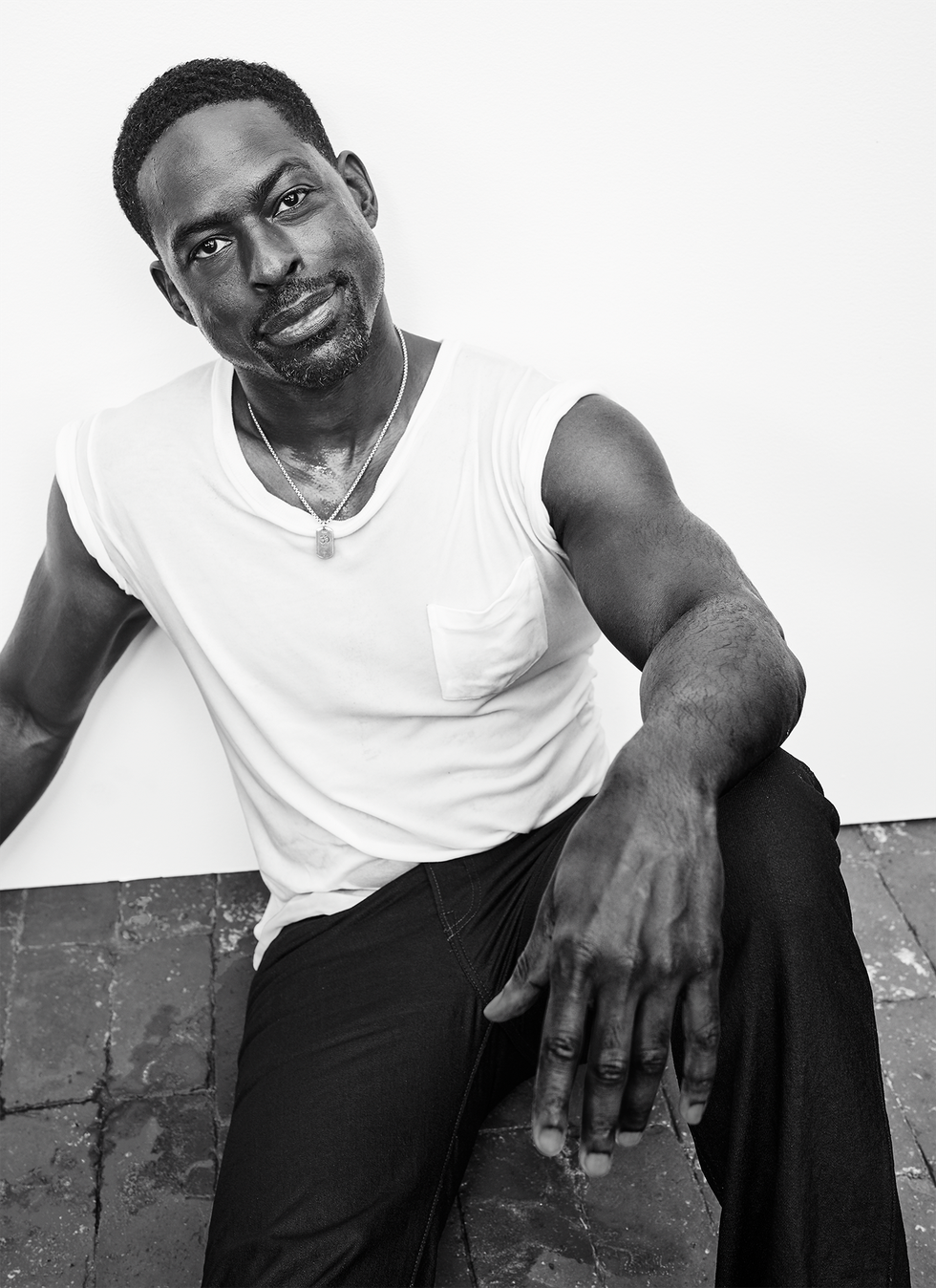

Brown is in Telluride, but when I meet him, he’s not doing all the networking and selfie taking and For Your Considerationing that Oscar hopefuls usually do at these things. He’s at a downtown condo complex, inside a small gym with a disturbingly low ceiling. The sweat-glazed, six-foot, 190-pound Brown is already a few miles into a vigorous run on a treadmill set against a mirrored wall. He looks more like a slot receiver than an actor, and he invites me to take the open treadmill next to his, with a mischievous but welcoming look. He promises not to have us breathing too hard in this thin air.

Before long, he’s on the floor and I’m laboring to maintain my balance through sets of bicycle kicks and Russian twists. (“Try to focus on form, not reps,” he says.) Then trembling through sets of chinups. (“Pace yourself now.”) Then trembling even more through sets of dumbbell lifts before I finally tap out with a bum left shoulder. (“You know, swimming would really help that. . . .”)

All the while, with metronomic consistency, Brown hisses and growls and roars straight past the soft targets he sets for me. You could waltz to the sound of his head butting against the ceiling during his chinup reps. By the end of our hour-long workout, I am fried. “Really?” Brown asks with a deep belly laugh. “I’m sorry! I saw you working really hard.” When I ask how the workout was for him, he says, “There was no pain for me. But listen, I have friends that I will enlist to work out with me, and they’ll be like, Yo, Brown, you need to calm down. You know you’re 43 now. And I’m like, Yeah, age ain’t nothin’ but a number.”

IT'S POSSIBLE THAT this is the most that any journalist has written about Brown in a profile without once mentioning This Is Us. (Four hundred and eleven words, for the record.) It is the show that made him famous and rich and prime Internet-boyfriend material, and he came to it after busting his ass in relative obscurity for two decades in the New York theater scene and cobbling together medium-sized roles on TV dramas like Third Watch and Supernatural. Then, around the time he turned 40, everything clicked. First he emerged as the breakout star of FX’s The People v. O. J. Simpson: American Crime Story (2016) for his portrayal of prosecutor Christopher Darden. That same year, he booked a lead role on the NBC drama This Is Us. He earned an Emmy for his performance in 2017, which marked the fourth time in the awards show’s 69-year history that an African-American had won outstanding lead actor in a drama series.

What’s more, Brown didn’t win for playing a slave or a drug dealer or a magical Negro (think Michael Clarke Duncan in The Green Mile) or the other kinds of roles for which black men are typically nominated. He won for his portrayal of Randall Pearson, the smoothie-drinking, daughter-raising, weather-futures-trading ballast of the otherwise all-white Pearson family. (Brown’s character is adopted.) With profound and often teary sincerity, Brown plays Randall as strong and smart and sensitive—a breakthrough for black male characters onscreen, a breakthrough owing in part to the vision of creator-showrunner Dan Fogelman (who is white) and his willingness to collaborate with Brown to hone the character. “I share things from my past that directly impact the way in which young Randall is written,” Brown says. That includes not getting a chance to say goodbye to his father, who died when Brown was ten—a moment of closure that came in the show’s pivotal “Memphis” episode in season 1.

Range comes naturally to Brown, who’s as comfortable posing in nothing but a bath towel on social media to promote the 2018 dystopian action thriller Hotel Artemis (note: his wife, the actor Ryan Michelle Bathe, filmed that video) or taking his shirt off on The Ellen DeGeneres Show as he is delivering the 2018 commencement speech at Stanford: a funny, emotional, and playful 30-minute call for students to let their “light shine” by embracing their passions for the broader good. (Incidentally, as we part company in Telluride, Brown is stopped by an older nerdy white guy—glasses, cashmere sweater, probably watches This Is Us—who was in the audience that day for his daughter’s graduation, and he thanks Brown for the wise words. It’s Bill Gates.)

If you look at the past three years of Brown’s life, and you spend a day with him and watch as he pounds pullups or BS-es with Bill Gates, you get the distinct impression of a man who has it figured out: stature, talent, a strong black family with two healthy boys (Andrew, eight, and Amaré, four), and a booming career that he attributes to “divine conspiracy.” Not only does that career show no signs of slowing down—he's voicing Lieutenant Matthias in Frozen 2, out Nov. 22—but it also seems as if Brown could do just about anything at this point and still come out on top.

And a black man like me—who’s pushing 40, who works out less and less, who mostly grinds in obscurity in hopes of his own breakthrough, who wonders if there’s still time to become his best self for his newborn son, and who watched Brown on Lifetime’s Army Wives (on which he played the male spouse in the friend group)—can’t help but be inspired. When I tell Brown of the long journey I made to this mountaintop just to receive wisdom from him, he laughs sheep-ishly and says, “Come on, bruh.” But he gets to talking about how he’s “expanding my definition of self” and about how life is “not about putting yourself in any kind of box.” Then he hits me with this, the real goal a young black man should have in his life: to live to 100.

A THREE-YEAR VARSITY letterman in football who also played basketball and ran track at St. Louis Country Day School, Brown entered his first triathlon in South Carolina about eight years ago, when he was a hardworking actor looking to push himself. “It was short distance,” he recalls. “A third of a mile in the pool, 14 miles on the bike, and then a 5K run.” There he was approached by an 80-something entrant. “He was like, ‘How ya doin’, young fella? This your first time out? Have a great time today.’ ” The triathlon took about an hour and a half. And when Brown beat the man by only 15 minutes, he came away more impressed with the old guy’s performance than with his own. “Once you see that as a possibility, you know that it’s something that you can attain for yourself.”

Growing up in St. Louis, Brown didn’t have many examples of vibrant elderlies in his life. He doesn’t know of a man in his immediate family who has lived past 65. His father died of a diabetes-induced heart attack at 45. “I just cried. I just cried. I miss him. Pops would’ve loved this stuff,” says Brown with a wistful look, referring to both all the sports he played in high school and his acting success. He tells me how he used to go by his middle name, Kelby, until his mid-teens, and how part of his grieving process involved embracing his full name. “Sterling always felt like an old man’s name because it was my old man’s name,” he says. “But now it’s my name.”

To hear his son tell it, the elder Sterling Brown Jr. was the quintessential cool dad. He cooked French toast for breakfast and sweet potatoes on Thanksgiving—his boy’s favorites, of course. He rode around in a pink 1972 Cadillac Eldorado blasting Michael McDonald on the eight-track. Most days, he was more best friend than father. “We would do dumb shit like fart in each other’s faces in bed, just try to catch each other off guard,” Brown says. When his mother wasn’t around, they’d binge-watch movies, including R-rated classics like The Terminator and Prizzi’s Honor. His father was a sucker for sappy moments. “Crying has never been a thing for me, like as a way to not be masculine,” Brown says. “Because my dad would watch a movie and it was just boo-fuckin’-hoo all the way through the whole thing. We would both be crying together, whether it was an animated movie or whatever. That was never forbidden or taboo. I was allowed to feel, because he felt.

“I think when Pops passed, I had sort of a recognition of the fact that 45 was young,” Brown continues. Mortality is something he’s acutely aware of. In his early 30s, he read Healthy at 100, a book by the ice cream scion–turned–nutritionist John Robbins that examined the habits of the world’s centenarians. Brown knows well the odds against him hitting 80, much less triple digits. Black men are in worse health than almost any other demographic in the United States. They’re more likely to be obese. They experience disproportionately higher mortality rates for many of the leading causes of death, not least cardiovascular disease and prostate cancer.

Making it to 100, for Brown, means sticking to a plan built around a daily exercise regimen heavy on calisthenics and hoops, a diet rich in grains and greens, and at least 20 minutes of meditation a day. He celebrates his birthday with a ten-mile run. “I just don’t want to give in to the statistical analysis that says that is my fate,” he says. “So I try to do things as proactively as possible to ensure that I’m around to see my children’s children and be of value to them when they come into the world. There’s so much to live for, and I don’t want to sell myself short by thinking I don’t have a right to longevity and vitality any more or less than anyone else.”

It doesn’t help that men in general tend to take a laissez-faire approach to their health. “Men want to suffer through stuff,” he says. “It serves us in certain circumstances, and in others we leave well enough alone for too long. I mean, if we’re looking at something as simple as prostate cancer and being able to check oneself, and the sort of fear or discomfort that the community at large may experience due to good old-fashioned homophobia—there’s foolishness that keeps us from living our best lives.”

But Brown believes some of the cultural barriers can be overcome with a bit of positive reinforcement. “So many young black men are into sports,” he says. “And then for whatever reason [as adults] they see sports as no longer being a part of their life. So when the sport is removed, the tenets for living a physically fit life aren’t necessarily in place. More of us have to learn how to carry the tenets that we learned that made us want to be competitive in that sport to just be competitive in life and maintain fitness. There are benefits beyond the game.”

As a teenager, Brown was recruited to play football at Claremont McKenna College but instead went to Stanford and majored in economics his first two years. In the summer, he interned at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. “I was always good with numbers,” he says. “I was the AP Econ guy. I thought making money was it.” He had acted in high school and relished his time onstage, but the idea of making it a career was laughable. “I thought it was something that only people who didn’t have to make a contribution to their families were allowed to do. I gotta help.”

Then a Stanford professor visited his dorm in search of students to audition for a school production of the August Wilson play Joe Turner’s Come and Gone. Brown went for it, landed the lead role, and immediately knew he had found his life’s passion. “Even though I was spending another two or three hours a night memorizing lines, my grades got better,” he recalls. “You know how the work is work but it doesn’t feel arduous? That’s something you have to pay attention to.”

AFTER STANFORD, Brown went to grad school for drama at NYU—where, apparently, being the strong man on campus had less value. “My teachers told me to stop lifting weights,” he says. “I was like, ‘What are you talking about?’ And they were like, ‘It’s gonna be hard for things to pass through you with all this musculature. So for emotion, for feelings to flow through, you have to be a vessel, a sieve, rather than something that is heavily armored.’ ” He stopped lifting. Started doing yoga. Shifted the focus of his workouts from brute strength to cardio. He would say things like, There’s no need for me to be swole and outta control. In his early theater days, he was encouraged by the many different examples of black male humanity he saw. “There’s a wider breadth of who you can be onstage than was allowed on the camera,” he says. “Denzel Washington, Sam Jackson, Delroy Lindo, Don Cheadle—all these dudes come from theater, and they weren’t jacked-up, crazy-looking dudes.”

Brown started going out for parts with more confidence, competing against the likes of Mahershala Ali, Mike Colter, and Anthony Mackie. “I remember auditioning for The Wire and being very close to Stringer Bell [which ultimately went to Idris Elba]. What’s been really cool for me in terms of the usual suspects is that it has been a situation of all love. We were like, Somebody’s gonna get the gig. I hope it’s you.” He considered himself lucky to work regularly enough to cover the bills in his 20s. “At any point 90 percent of all the acting-union members are unemployed, and you’re just fighting to be part of the rotating 2 percent,” says Brown. “There’s so much rejection that you have to be willing to deal with and let it sort of roll off your back. There are people I know who are absolutely

brilliant who had to segue into something else in life.”

Of course, being married to a fellow actor can lead to jealousy. Brown met his wife at Stanford and makes the extra effort to talk through any feelings of envy with Bathe. “Ryan celebrates my success,” Brown says. “But sometimes it’s like, Damn, bro, when’s it my turn?” It doesn’t hurt that their boys could “give a flying Fig Newton” (Brown’s words) about their acting careers.

In Trey Edward Shults’s Waves (out this month), Brown plays Ronald, the hard-ass patriarch of an upper-middle-class black family who’s in perennial competition with his son, a standout high school wrestler. While his character is 180 degrees from the adorkable Randall Pearson, the vulnerability for which the actor has become known shines right on through. With Waves, Brown got to try something different, something new—which is more of a chance than he ever thought he’d get in this business. “For such a long time, you’re waiting and hoping for these crumbs from the table of joy,” he says. “Then all of a sudden people are like, What do you wanna do? What are you interested in? We wanna work with you!”

Reflecting on this, Brown riffs on the point of acting, why it is that he’s so passionate about what he does. “I want to hopefully give you some sense of inspiration, either to make the world a better place or for you to be a better person,” he says. “And so when I step into a theater, when I step on set, it is my sanctuary. It’s me and it’s not me. I’m a vessel for a story to be told, for a perspective to be illuminated.”

CUT TO TWO DAYS later. I’m back in the South Carolina Lowcountry, and the outlook on the home front is grim. My back is tight. My shoulders may as well be closed for repairs. Most days, I flit around the house like a hummingbird. Now I’m pinned to the couch like a feather in a nest. I can’t afford to lie here. There’s a hurricane coming, an evacuation order to heed. My family is depending on me, but leaving the mountaintop has been a helluva comedown, and I fear my vessel may be busted beyond repair. I wonder, What would Sterling K. Brown do?

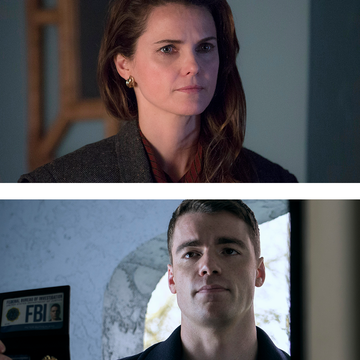

Weirdly, my mind tracks back to a story he shared about launching his production company—Indian Meadows, named for his old St. Louis stomping grounds. “[American Crime Story executive producer] Ryan Murphy was the first person I know of to say in order to have ownership over your career, you kinda have to tell your own stories,” says Brown, who is focusing on film and TV projects that have what he calls intelligent diversity. “I’m looking at people of color in the forefront. They can be best friends, too, but they gotta be in the forefront of the show.” (First up, he’ll costar with Kerry Washington in a thriller called Shadow Force.) Granted, on the surface this would appear to be an obvious career move for an actor on a hot streak. But Brown, as a former econ major who’s plugged into one of the most well-heeled alumni networks on the planet, would seem uniquely positioned to win, no? “I think you probably give me credit I don’t deserve,” he says. “Anytime you step into the unknown, there’s a degree of fear. But I do know that when the desire supersedes the fear, the momentum carries you forward.”

That last line lingers in my head awhile—until, suddenly, my arms are swinging my limp body off the couch. My feet are shuffling out from under tender hips as I drag outdoor planter boxes out of harm’s way and lift shutters onto windows. I take many breaks from the butter-thick humidity; at the end of the day, I pull through. Desire had superseded fear, with nothing left to feel but pride.

And yet it isn’t until later, when I’m bouncing my baby boy in my adrenaline-

charged arms from the safety of an Atlanta hotel room, that I fully appreciate what Brown means about the great potential an active lifestyle has to add zeros to a life. “It’s easier to maintain a level of fitness than it is to lose it and try to get it back,” he says. “You want to do enough that you feel like you’ve done something, but not so much that you don’t wanna do it again tomorrow. So it’s not about trying to kill yourself. It’s about trying to give yourself the inspiration to continue.” No doubt that kind of mind-body strategy can help keep a man young. Get used to it. Sterling K. Brown is gonna be around awhile.

Andrew Lawrence is a freelance writer, and has written for Sports Illustrated, The Guardian, The Atlantic, The Athletic, The Dallas Morning News, the Associated Press, Fortune, Southern Living, Austin Monthly, Complex, Cookie, BET.com, ESPN.com and The Classical. He is based in Beaufort, South Carolina.