- While most people think of postpartum mood disorders as a women's issue, nearly 10 percent of men have postpartum anxiety (PPA) or postpartum depression (PPD)

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder, or OCD, is a common form of postpartum anxiety

- For parents, postpartum OCD can manifest itself in terrifying, intrusive thoughts about being violent or even sexually abusive toward their own children

- Parents with postpartum OCD are not at risk of acting on those thoughts, but that doesn't change how difficult it is for men to live with them

Most new dads know how tough it is to get a baby to fall asleep. Usually, when they finally start to nod off, it’s cause for celebration. But when Ashley Curry's first child was born, bedtime was nothing less than terrifying.

“I’d get up to make sure that the blankets hadn't gone across the baby’s face once, then go back to bed,” Curry, now 49, recalls. “Then I’d go back and check again, then again. Then I’d just spend most of the night checking.”

Curry’s normal parental concern became a profound, constant terror. He would insist on bathing the baby himself, in case his wife “drowned him accidentally.” He constantly wondered whether he was his child’s biological father, even though he trusted his wife completely and had no reason to suspect otherwise. Worst of all, he’d spend hours obsessing over the possibility that he had inadvertently physically or sexually abused his son — even though the idea of hurting his child in any way was abhorrent to him.

For years, Ashley struggled with these thoughts alone, without seeking counseling or treatment. When his daughter was born a few years later, his symptoms worsened. He started having severe panic attacks. He couldn’t sleep. He lost more than 25 pounds. “I was really, really unwell,” he says.

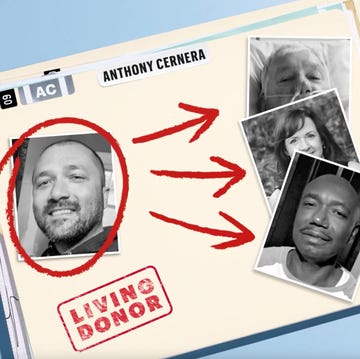

Convinced he was on the verge of a nervous breakdown, Curry went to the emergency room. When he told doctors his symptoms started after his first child was born, he was retroactively diagnosed with postpartum Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD), a form of OCD that affects new parents. It most often manifests itself in intrusive, disturbing thoughts about the baby — even though the parent has no desire whatsoever to act on those thoughts.

Curry was relieved. He had struggled with these terrifying thoughts for so long without knowing why, or telling anyone about them. “Knowing what was wrong was half the battle for me,” he says.

Most people have disturbing thoughts from time to time. The most common example cited by OCD scholars is someone standing in front of a subway platform and suddenly thinking, “What if I just pushed the man next to me in front of the train?” But most people tend to forget about these intrusive thoughts, the images drifting out of their brains just as quickly as they entered them.

For people with OCD, however, such violent intrusive thoughts are more than fleeting. They are constant, unrelenting, and often extremely disturbing. While most people would just laugh off the sudden urge to commit a violent crime on a subway platform, dismissing it as a brain fart, someone with OCD could comb their memory for hours afterwards to “check” that they didn’t act on that thought, then go back to the station later to look for evidence.

When people exhibit OCD symptoms after becoming a parent, it’s known as postpartum OCD. Postpartum OCD falls under the umbrella of postpartum anxiety (PPA), one of many mental health issues that can afflict new parents.

Postpartum mental health issues are relatively common among new moms: according to the American Psychological Association, approximately one in seven women struggle with postpartum depression (PPD) or PPA, and celebrities like Hayden Panettiere and Chrissy Teigen have spoken openly about their struggles with the condition. But we don’t often hear about new dads struggling with postpartum mental health issues — even though one study estimates that approximately one in 10 new dads has PPA or PPD.

“When we think postpartum, we think of moms and we assume it’s a result of pregnancy hormones,” says Dr. Jonathan Abramowitz, a clinical psychologist and professor at UNC Chapel Hill who studies anxiety disorders, including postpartum OCD. “[But they are] often related to this huge increase in responsibility that comes with having a baby."

Abramowitz has been studying postpartum OCD for years. In fact, it was his own intrusive thoughts after his first child was born that prompted him to study postpartum OCD in the first place.

“One night, I got up when the kid was a week old,” he recalls. “I’m feeding her, it's like 2:00 in the morning and my wife is asleep. I’m patting the baby on the back and I’m thinking, ‘Oh, my god, what’s stopping me from beating the shit out of this kid?’” When Dr. Abramowitz spoke to a colleague who was also a new parent, he was surprised to find that she too had experienced thoughts about driving a pencil into her baby’s soft spot.

In 2007, Abramowitz authored a study assessing whether new parenthood was a risk factor for OCD. Shockingly, he found that 60 to 90 percent of new parents had experienced such intrusive thoughts. “We found that almost everybody reports having unwanted thoughts about a newborn baby, because they look so vulnerable and they’re so cherished,” he said.

Of course, not every parent who experiences such thoughts has postpartum OCD. It’s the frequency and intensity of the thoughts that differentiates normal behavior from postpartum OCD, as well as engaging in compulsions, or “safety” behaviors, that serve to alleviate their anxiety — for instance, checking their child over and over again for signs of harm, as Curry did.

People with postpartum OCD might also try to avoid their children, causing them to “not change diapers or not spend time with the baby,” says Dr. Carolyn Rodriguez, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University. They also might try to over-correct by spending all of their time with the baby, fearing that someone else might hurt them.

“I became very protective of the baby, so I took over quite a bit,” Curry says. “People would say, ‘Oh, he’s a fantastic father!’ But actually, I was being over-responsible.”

It’s also not uncommon for new dads with postpartum OCD to obsess over the prospect of sexually abusing their children, even though the thought of causing them harm is anathema to them. “I worked with a dad who was afraid to be left alone with his baby: 'What if I molest the baby? What if I touch the baby on the genitals when my wife isn’t around to stop me?’,” Abramowitz says.

But it’s crucial to note that however dark their thoughts may be, men with postpartum OCD are not at risk of acting on them. “These intrusive images are unwanted, so they cause a lot of distress,” says Rodriguez. “They go against what they actually feel in their heart.”

In this sense, postpartum OCD is very different from postpartum psychosis, a rare and severe postpartum condition that causes new parents to suffer from delusions that compel them to harm their babies. (The condition allegedly caused a 32-year-old new mom in St. Louis, Mo. to kill her newborn daughter and husband before taking her own life last month.) “People [with psychosis] don’t recognize that their thoughts are actually harmful,” explains Rodriguez. By contrast, people with OCD are fully aware of the disturbing nature of their thoughts, which only makes them feel even more guilty for having them.

It’s also crucial to note that while people with a history of anxiety or depression may be at increased risk, anyone can develop a postpartum mood disorder, regardless of their mental health history. Before becoming a father, Curry had never been diagnosed with a mental illness, though he had occasionally struggled with intrusive thoughts. After becoming a parent, however, these thoughts became constant and unmanageable. He constantly checked his children for injuries, frequently asking other people if they looked “normal.”

“The images flash up and it's like they’re actually real memories, so you have this urge to keep going over and over them and work out whether you have done these things or not, but you can’t get a solution,” he explains. “It's like playing Whack-A-Mole: you knock one down and another one pops up.”

“You sort of have this man thing that you’re supposed to be the strong person. So you just carry on as best as you can."

Of course, when new fathers have troubling thoughts — especially thoughts about sexually abusing their own children —, they may fear being judged or deemed a threat to their children's safety. This fear of judgment, combined with the societal pressure on fathers to appear masculine and “strong,” leads many men with postpartum OCD to suffer in silence.

But ignoring the symptoms of OCD just isn’t an option, says Fred Penzel, PhD, a psychologist with 35 years of experience treating OCD. “You're not going to wake up one morning and find that it's gone away,” he told MensHealth.com. “This is a chronic problem that requires serious treatment.”

According to Penzel and Abramowitz, the best way for dads to make sure they get the help they need is to contact a therapist who specialises in OCD (the International OCD Foundation keeps a list of OCD specialists).

The most common form of treatment for postpartum OCD patients is exposure and response prevention (ERP), in which patients rank the things that scare them (for example, holding their baby, or changing their baby’s diaper) from least to most distressing. They gradually work through the list, performing each action with the support of a therapist.

ERP is not a cure for OCD, nor does it get rid of the intrusive thoughts entirely. The point is to prove to patients that they are not at risk of harming their children, says Penzel. “We get people to read stories about people who harm their children as a way of confronting their thoughts,” Dr Penzel explains. “We try to list all of the things that can set a person's anxiety off. It's all about building tolerance.”

Following Curry's trip to the emergency room, he underwent nine months of ERP to treat his OCD. He emerged from the treatment symptom-free. “Eventually, life got back to normal again," he says.

But he urges new dads grappling with these thoughts to seek treatment immediately. “You sort of have this man thing that you’re supposed to be the strong person,” he adds. “So you just carry on as best as you can. But really, until you get help, you’re just going down a slippery slope.”

For OCD support and advice, contact the International OCD Foundation. If you or someone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).