Our health service is unwell. You’ve read the news stories – staff at breaking point, pitiless waiting times, patients languishing in corridors. The problems it faces are deep and knotty, though hope is not lost. Whether the solutions lie in smarter funding, technological innovation, or even our own actions, there are bright minds at work to find them. For this series, MH assembled a team of field-leading thinkers to share their strategies.

Is it a case of whither the NHS, or wither the NHS? The crisis in the post-pandemic world is evident. A combination of underinvestment and heightened demand has led to massive waiting lists, derogated care and even crumbling infrastructure – witness the grotesque news in recent months that there have been almost 500 leakages of raw sewage into hospital wards. As the ambulances queue up in A&E, with trolleys in the corridors resembling some real-life game of Candy Crush, wannabe patients sequestrated in their homes waiting, despairingly, for long-postponed elective surgeries. The conclusion is surely inescapable: what’s needed here is a massive injection of adrenalising cash into our sclerotic health system, so that it can remain a beacon in a darkening world. ‘Our NHS’: the national service that didn’t just protect the abstraction of nationhood, but the very concrete, bodily reality of man-and-womanhood.

Okay, fine, but pandemic or not, here’s the problem: the demand for the sort of healthcare offered by the evolving western model – which remains fundamentally instrumental: we cure you by doing/giving things to your body – continues to grow exponentially. Meanwhile, the capacity to pay for this is necessarily incremental. And the ever-widening gap between the perceived capacity of the NHS to cure people of pretty much whatever ails them (even unto death itself) and the reality of the care on offer, is experienced by Britons as terrible privation.

Yes, the pandemic put great pressure on the NHS. Yet it’s the associated social care crisis that really gives the lie to the idea that there’s any fundamental solution to the problems of an ageing, obese population that doesn’t exercise, and drinks, smokes and takes too many drugs, in simply investing more in medicalised approaches. Yes, yes, dear reader, I know this isn’t you. But then it’s the first rule of good empathetic medical practice that no patient ever considers himself to be a statistic.

Unfortunately, the disconnect between this attitude and a public debate about healthcare founded entirely on the quantification of resources is only too clear. Successive governments impress upon voters that they’ll protect ‘our’ NHS. Really, the health service stands proxy for whatever notion we have left of a mutually supportive civil society – so for ‘commonwealth’, read ‘common health’.

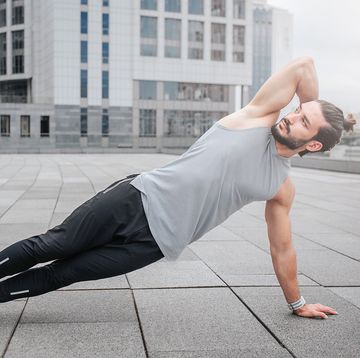

The solution doesn’t lie in this paradigm at all, but in a taking back of responsibility for health on the part of the individual. Yes, it’s easy to be bedazzled by what medical science can do – it does, indeed, approximate to magic when compared with the healthcare practices of the very recent past. But if we want to revert to a statistical view rather than indulging in individual credulousness, the fact is that if we, as a society, halved our drinking, quadrupled our exercise and cut out refined sugar altogether, both the crises in social care and the NHS would belong to the past quite as much as excruciatingly painful dentistry and septic obstetrics.

I write this not as a statistic myself, but as an individual whose very life currently depends on pharmaco-wizardry. If I didn’t take drugs that specifically target the stem cells in my bone marrow that go on to overproduce white and red blood cells and platelets, I would die from the underlying cancerous condition in pretty short order. Of course, basing any opinion on an empirical sample of one is a big mistake – and besides, while my own treatment has been exemplary despite the pandemic, I know this is due to such specifics as where I live (within a mile of one of the foremost teaching hospitals in the world) and, frankly, how I speak. Educated, middle-class doctors still have an unconscious bias to look out better for their own.

So, I speak not for myself, but in the spirit of ‘our National Health’. And I say this: if you really believe in universal healthcare, free and on demand, then you’re a communist by definition. And as such, you should look to nations such as Cuba for a radical reconfiguration of health services towards prevention, community care and education in self-reliance. Good luck with that one!