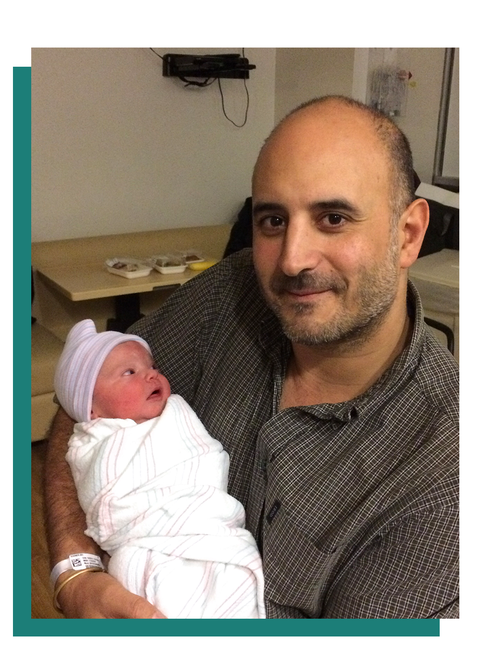

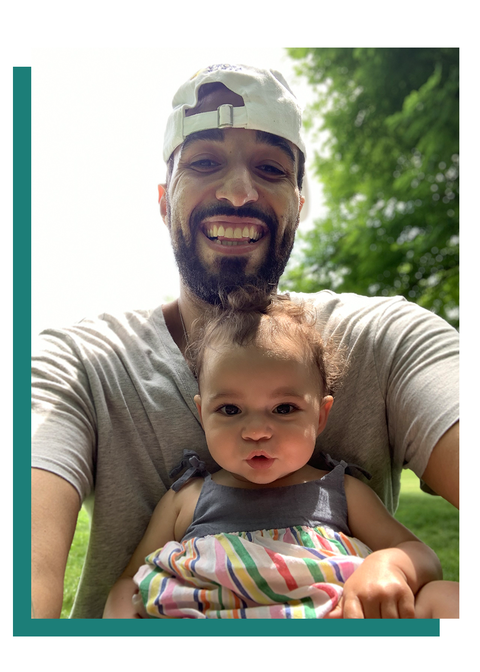

SHORTLY BEFORE his daughter was born last year, Mo Greene, 35, then working in apparel sales, asked his boss if he could take paternity leave. The boss told him that if he did, he’d be fired. Then Greene’s daughter Aurora was born in July, and they fired him anyway, while restructuring the company. His wife had a complicated delivery, so Greene suddenly found himself having to support her and the baby while also trying to find a new job. “It really fucked up my head a lot,” he says. A month in, he started having problems. He began drinking more at home. He and his wife started arguing more frequently, and he became so lonely that he’d look for excuses to go to the corner store just to talk to someone. “It was like I was like a completely different person,” he says.

Greene had always prided himself on his ability to handle his problems alone. “It’s very rare that I ask anybody in the world for help, which is maybe not the best thing,” he says. But that approach collapsed with new pressures at home. “Every time I’d think I have it under control, something would happen that triggered it,” he says. There’d be an argument over bathing the baby, say, and Greene would suddenly find himself thinking, “Maybe I am fucking incompetent and don’t know what I’m doing with this, and I’m a terrible fucking person,” he says, “and it’d go back into that spiral of loneliness, darkness… feeling like there was no outlet for me to express what was going on.”

When Jonah Barnett, 41, was growing up working-class in Norfolk, Virginia, he lost several friends to drugs. His parents were divorced and he was raised by his mother and stepfather. Then, almost seven years ago, he lost his mother. Two years later, his little brother died from an autoimmune disease that no one knew he had. Barnett worked as a waiter and bartender for years before enrolling in nursing school in 2019, about the same time he and his wife found out they were pregnant. This was a lot to handle, but he felt hopeful. When his daughter Willow was born in January of this year, the birth was “perfect,” he says. But shortly after, he started to come apart, inexplicably breaking into sobs.

One day he was walking home when Chris Cornell singing Audioslave’s “Like a Stone” came on his phone. Barnett suddenly found himself paralyzed in the street, crying inconsolably as a series of images flashed through his mind. “It was like an old-school cartoon flip-book of these little scenes of Willow and my wife and all these great things,” he says, “but interspersed was this set of scenes from my childhood, and things that I wanted my mom to be there for, and all these other things that were making the goodness into sadness. And that’s when it hit me: It was just like, Who is there? There’s nobody left.”

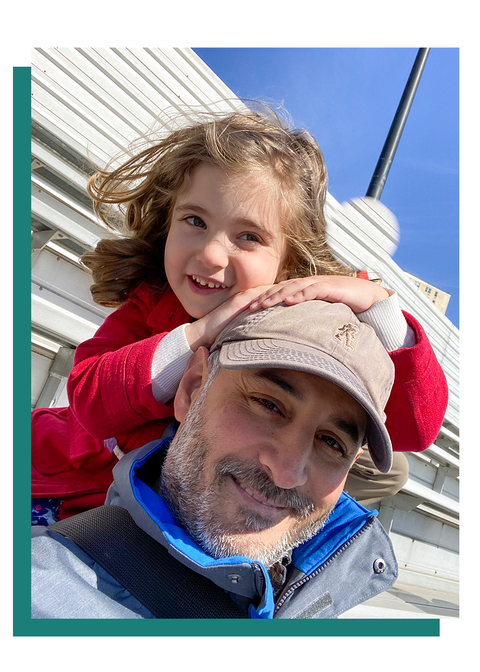

Five years ago, David Erickson, now 51, was in a pretty good place. He had a job he liked in facilities management, and he and his wife, who were expecting, were in the midst of buying a house. Then, just after his daughter Ellen was born in the fall of 2015, his job was terminated. His wife went back to work part-time, and he stayed home to watch the baby, while also coordinating the move to the new place and trying to start a photography-related consulting business to bring in some money. The uncertainty wore on him. “I was like, ‘We’re moving, I don’t have a job, and I’ve got a baby. What the fuck?’”

Erickson struggled to be the sort of engaged parent he wanted to be, and this led to feelings of failure. “I wasn’t equipped to do my model of parenting,” he says. “My dad did a lot of parenting, but in a more indirect way. It wasn’t like, ‘Hey, son, this is how you change a diaper.’ There was no father-to-son hand-me-down of how to be a parent.” When he began working again, that sense of failure crept into his professional life. “There were some dark times where I was with my daughter and I was thinking about work, and then when I was at work, I was only thinking about my daughter,” he says. “I was going into that cycle of Well, suck it up, asshole, you’re a man—get with it.”

He had suffered from depression in the past. But this time, he decided he’d had enough. He started seeing a psychologist, and it was then that he learned he was suffering from something that to previous generations, and even to newer ones, might seem surprising, or embarrassing, or even ridiculous, but which put him—along with fellow New Yorkers Greene and Barnett—on a vanguard of sorts. He had postpartum depression. They all did.

Paternal postpartum depression (or paternal PPD) is a delicate matter to discuss in 2020, a time in which historical injustices against women have been brought to the fore, and when mothers and fathers are struggling to figure out a more equitable way of parenting, often while working. Depressed dads might worry they are failing as fathers, as partners, or as men. They might believe they have no right to confess to struggling—that people will think they’re trying to steal something away from mothers, who have been handling the bulk of parenting duties since time immemorial and, of course, actually had the baby. As Erickson put it, “Generations of women have been dealing with these things, times ten, and here I am, a white privileged male who has lived a pretty nice life—what the fuck do I have to complain about?”

And he’s right, to a point. And that point is the one where these concerns, however well-intentioned, keep fathers from getting help. Because we know now, thanks to an emerging body of research, that while old-fashioned stoicism is very effective in some situations, it can fail utterly when a dad becomes depressed, doing lasting damage not just to him, but to his partner and children. So what can men do? They may not like the answer.

IT IS TO the eternal detriment of the (yes, largely male) medical and mental-health establishments that they took so long to take postpartum depression in mothers seriously. “Clinicians since Hippocrates have noted an association between the postpartum period and mood disturbances,” Laura Miller, M.D., medical director of Reproductive Mental Health for the Veterans Administration, wrote in 2002. And yet it wasn’t until 1994 that postpartum depression was included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM, the bible for mental-health practitioners. After many years of doctors ignoring it, shrugging it off, or even mocking it, the world has finally come around and accepted that maternal postpartum depression is a problem worthy of diagnosis, treatment, and study.

The issue now is that postpartum depression is so closely identified with mothers that few expect to see it in fathers—not the men themselves, not their partners, and not even those comprising the gauntlet of birthing professionals all expectant parents must endure en route to having a kid. But as a small but growing number of studies over the last decade and a half have shown, paternal postpartum depression is a real problem, and it is occurring in significant numbers—regardless of your sexuality, or whether your children are biological or adopted.

Some researchers have estimated that it may affect as many as a quarter of all new fathers, although a growing consensus hovers at around one in ten. The reason those numbers vary so wildly is because so little research has actually been done on paternal PPD. There have been no clinical trials to establish treatments for it, and it is not included in the latest edition of the DSM.

There have been some appeals by experts over the years to take paternal PPD seriously, but those calls have been largely ignored. In January, three leading researchers, Tova Walsh, Ph.D., Neal Davis, M.D., and Craig Garfield, M.D., published a piece in Pediatrics—the influential journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics—urging pediatricians to screen for paternal PPD, just as they do for maternal postpartum depression. “It is now critical to recognize paternal depression as a community of pediatric providers and ensure consistent screening, referral, and follow-up,” they wrote.

Research shows that new dads are roughly twice as likely to be depressed as an average man of comparable age—and they see as much as a 68 percent increase in depressive symptoms within five years of having kids compared with nonfathers. This is because parenting can be, frankly, depressing. Especially for those with a history of depression (see Risks of Paternal Postpartum Depression below).

Detecting postpartum depression in men can be tricky, however, because of some subtle differences. Maternal postpartum depression is often tied to hormones, and though there is some evidence that paternal PPD may be linked to a dip in testosterone and other hormonal changes experienced by new fathers, it is more an umbrella term for acute depression or anxiety disorders occurring after a birth. As with moms, affected dads might experience depressed mood, a loss of interest, fatigue, disordered sleep, unusual fluctuations in weight, or recurring thoughts of suicide and death.

But paternal PPD is different in some key ways. While symptoms of postpartum depression in women usually emerge soon after the birth, fathers can take up to a year to show symptoms. When they do, the symptoms are often masked by emotional withdrawal, anger, cynicism, indecisiveness, substance abuse, or compulsive working or exercising—behaviors that, to the untrained eye, can read more like misfiring male stoicism than signs of postpartum depression.

While the research on paternal PPD remains limited, one thing is abundantly clear: Having a depressed father around is bad for everyone. Depression can negatively affect a father’s ability to properly support his partner. The stress it causes her can hamper her ability to recover from childbirth, bond with her infant, and nurse. He can even become violent. According to a 2000 Swedish study, a quarter of new mothers reported being threatened or physically or sexually abused by their partners in the postpartum period. Among that group, 69 percent of the women stated that the abuse started after delivery.

For all the harm it can visit upon a man’s partner, paternal PPD reserves its worst stuff for children, correlating with a raft of social, emotional, and behavioral problems in kids. Infants of depressed fathers show heightened levels of distress. They cry more. Depressed fathers spank their children more and read to them less; they are less sensitive to their kids, more hostile, and on the whole less involved. And living with a chaotic or withdrawn parent causes elevated levels of the stress hormone cortisol in infants, which can lead to behavioral problems and stunt the development of the body, brain, and immune system.

Men are already less likely to seek help than women, and fathers are less likely to seek help than childless men. This is exacerbated by the fact that health-care providers and even some mental-health experts still roll their eyes at the idea that a man can experience postpartum depression. “You still have institutionalized stigma of men who struggle emotionally,” says Michael Addis, Ph.D., a professor of psychology at Clark University who specializes in men’s mental health. “Even among mental-health professionals and researchers, it’s just hard to take it as seriously when it’s a guy who’s going through something like postpartum depression.”

Nicole Altenau, RNC-OB, a veteran labor and delivery nurse and an administrator at Monmouth Medical Center in New Jersey, saw this firsthand. After watching her husband experience symptoms of PPD, she published an article on paternal postpartum depression in the journal American Nurse earlier this year. When she told peers she was working on it, the reactions ranged from confused to contemptuous. “I don’t think it really even occurred to them,” she says. “They were like, ‘Ugh, come on.”

All these cultural and institutional factors combine to form a sort of loop. Fathers are trying to do more than previous generations, but they’re not prepared. When they struggle, they are less likely to seek help. If they don’t seek help, doctors, nurses, and therapists are unlikely to gain firsthand experience with paternal PPD. If these professionals don’t see it regularly, they won’t know to look for it, and urgency won’t gather around the issue. Without urgency, you can’t get research funded. Without research, medical professionals will remain either skeptical or unaware that paternal PPD even exists, and it will continue to quietly ravage men and their families.

MO GREENE HAD an epiphany while he was giving his daughter a bath about six weeks into his depression. “I was kind of going through the motions, and then she made a noise, and I saw her,” he says. “She looked at me, and something in her eyes kind of pierced my soul, and I was like, All right, I gotta figure this thing out.”

He didn’t seek professional help, or even talk to his wife about his depression. “I just tried to fix it myself,” he says. As a highly social guy, that meant getting over his aversion to asking for assistance by reaching out to friends who were also fathers, asking, “Yo, is this normal?” Some friends were shocked that such a larger-than-life character could get depressed. “Really?” he recalls them saying. “You? No way!” He found himself in the curious position of having to convince them that, yes, he was actually having a hard time.

He also started attending a meeting called Dad 411, organized by Park Slope Parents, a wildly successful group founded in Brooklyn in 2002 to support parents through meetups, newsletters, message boards, classifieds, and so forth. Greene and his wife were members of the organization, which began offering a dads group in 2011—recognizing the value of creating a space where fathers could talk to other fathers—but Greene personally never saw a need for it. “I was like, ‘This is stupid. I’m never going to use any of this shit,’” he says. “And then it all hit me and I was like, ‘I need something, so maybe I should go try this.’”

Dad 411 meets monthly and resembles a classic community support group. Expectant dads and new dads and experienced dads hang out and ask questions, seek advice, and talk about their problems. For Greene, this was difficult. “I didn’t want to seem like things were going wrong,” he says. “And I didn’t want to seem like I was doing something incorrect.” But eventually he found it reassuring to know he wasn’t the only one having a hard time. “It’s knowing that like, okay, like I’m not a complete fucking psychopath,” he laughs. “Like there are other people that are doing other things to cope with what they’re going through.”

Erickson was also a member of Park Slope Parents, and he used it to put out a call asking if there were any fathers who wanted to take a walk in the park. Some did, and it turned into a weekly thing, which he found helped him overcome depression. “Just being able to have community made a really big difference,” he says. “It’s like, okay, I’m not alone…. Other people have figured this out, so I can do that, too.” Soon he was also organizing Park Slope Parents game nights to bring in more dads, whose shared experience he’s come to appreciate. That outreach, coupled with seeing a therapist, helped immeasurably. “I had community, and I had therapy,” he says. “I was just like, ‘Okay, I’m not worthless,’” he laughs.

Barnett is also a Park Slope Parents member—we met, like the other men, when I put out a call through the message boards—but he’s less involved. For him, the turning point was a simple revelation. “You’re going to make things even worse for the kid if you don’t deal with the situation,” he says. “The whole point is to be a good dad, bro. So fix yourself.” He set out to do just that. Before his baby was born, Barnett had done yoga and meditation, but he’d let those lapse. He recommitted to both, which helped him deal with the stress and feelings of being overwhelmed. He’d also seen a therapist in the past but stopped that as well when life got too busy. He called her again in April. That has helped enormously, he says, in part because the sessions have helped him identify what was triggering him—his losses, his rough childhood—and taught him skills to find quiet and keep perspective when he starts to spin out.

THERE ARE SOME glimmers of progress in the medical world. After Walsh sent up her flare about the need for more aggressive screening, she says she began hearing from pediatricians and advocates who have been trying to get more providers in their area to screen dads. Walsh organized a webinar recently on the role of fathers in children’s health that featured discussion of paternal depression. Nearly 1,000 health-care and child and family service providers signed up to learn more. “This level of interest is exciting and hopeful,” she tells me.

Promising work is also being done by institutions. Lisa Tremayne, R.N., the founder and director of the Center for Perinatal Mood and Anxiety Disorders at Monmouth Medical Center in New Jersey—one of the country’s few dedicated units for postpartum depression—says the center has served 5,000 women since its inception in 2015. But about a year ago, some men started showing up, too. One was a burly guy whose wife heard him crying in the shower and called Tremayne to ask, “Lisa, do men get this?” Tremayne said yes and contacted him. “He just broke down,” she says. He told her he was terrified he wouldn’t be able to provide for his family and thought they might be better off if he were dead. “We’ve been hearing women say that in the years we’ve been here,” says Tremayne, who suffered postpartum depression herself. “But he was the first man I heard say it.” Several more men have since come in for treatment, and Tremayne’s staff is now working on pamphlets to distribute to new parents coming through the hospital to raise awareness of paternal PPD.

Until the rest of the world catches up, though, it will fall to fathers to do what they may be loath to do: talk about it. “Normalizing it is key,” says the psychology professor Michael Addis, Ph.D. “On an individual level, men who are struggling with this need to take the risk of reaching out.” That doesn’t mean moaning about it to anyone within earshot, or engaging in pity contests with your partner. It means picking your spots. The dozen men I interviewed for this story all had success in seeking out other fathers to talk to and/or getting therapy—both of which experts point to as potential treatments for paternal PPD.

The experience of talking to other fathers was transformational for Mo Greene. He says he’s more confident as a parent and more attentive as a partner. “It’s really helped our relationship in general from a communication standpoint—to be more open with each other and talk about different things that we need and don’t need,” he says. “That’s been a huge benefit and something that wasn’t happening before.” The effect has been so profound that he launched his own podcast, Dad Hard with a Podcast, in which he has candid conversations with other men about fatherhood. “I’m trying to dedicate this next part of my life to try to help dads any way that I can,” he says. “Because it’s important. We all go into this blind and seemingly alone, because we’re supposed to be stoic and macho,” he adds. “It’s probably why all of our dads have fucked-up problems that they don’t deal with…. That’s a tough road to go down.”

David Erickson still feels the stress and tension of life, but his therapist taught him how to tell the difference between his emotional responses and reality, and the work has also made him a more emotionally attuned father. The last time his daughter came back upset after a play date, “I gave her a big old hug and just let her unwind,” he says. “I didn’t say, ‘What happened? Why?’ and drag her back. If I didn’t appreciate the fact that she’s having an emotional response, I couldn’t be that kind of father for her.”

Jonah Barnett has since planted a lettuce garden and continues to meditate, do yoga, and go to therapy to stay on an even keel, balancing the pressures of parenting and nursing school. His experience has taught him that the cycle of dysfunction he was a part of could be broken. “I’m not going to screw up my kid in the way that I was screwed up, because I’m aware of how I was screwed up,” he says. “And I’m aware that things don’t have to perpetuate themselves, and so I was just able to move past that.”

And then, finally, for the sake of full disclosure: There’s me. I struggled through a deep depression after the birth of our daughter four years ago, and I did exactly the wrong thing. I told almost no one and brazened it out, as I always do in the face of difficulty and pain. When I told a friend about it in the course of reporting this story, he was shocked. “You really do have an unnerving talent for obscuring negative emotions,” he said. I told him that in a previous life I’d have considered that a compliment. “I mean, look, it’s impressive, but destructive,” he added.

Eventually I emerged from it. But if parenting a toddler is hard—the average Tuesday contains a level of abuse and degradation that in a theater of war would constitute a violation of the Geneva Conventions—under COVID-19 it became borderline intolerable. We lost all our childcare, we were confined to our apartment, and we still had to work. And as I began to slide back down, I wisely heeded the advice of the men and women I spoke to for this story and did what I should have done a long time ago: I made an appointment to see a shrink.