FOR MOST OF his life, Anthony Abbate faced a dire reality. No man on either side of his family had lived beyond his 50s, mainly because of heart issues. It hung over Abbate like a time bomb: He was unlikely to see his 60th birthday.

As he got older, doctors urged Abbate to begin a workout routine that got his heart pumping. But the idea of cardio had always worried him. “Growing up, I was the chubby kid, the chubby nerd,” says Abbate, an architecture professor in Fort Lauderdale.

In 2005, at age 47, the first heart attack hit. Like his father and uncles and grandfathers, Abbate figured it would be the first in a series of attacks, with one sure to kill him. “After my first cardiac incident and stenting, I became so afraid of what would happen if I got my heart rate up,” he says. But that changed nine years ago, after his wife gave him a Christmas gift: a membership to a gym that had just opened in a nearby shopping center, next to an Asian-fusion restaurant.

This was the very first location of Orangetheory Fitness, which opened in 2010 at the forefront of what would become an exercise craze. Unlike the big-box gyms that once dominated suburban America, Orangetheory was part of a vanguard of new challengers offering group fitness classes with high-intensity interval training. It and other HIIT-based gyms, like F45 Training, Rise Nation, and Rumble Boxing, mix different types of cardio and weight training in short, difficult bursts, so you’ll keep your heart rate elevated while you burn fat and build muscle.

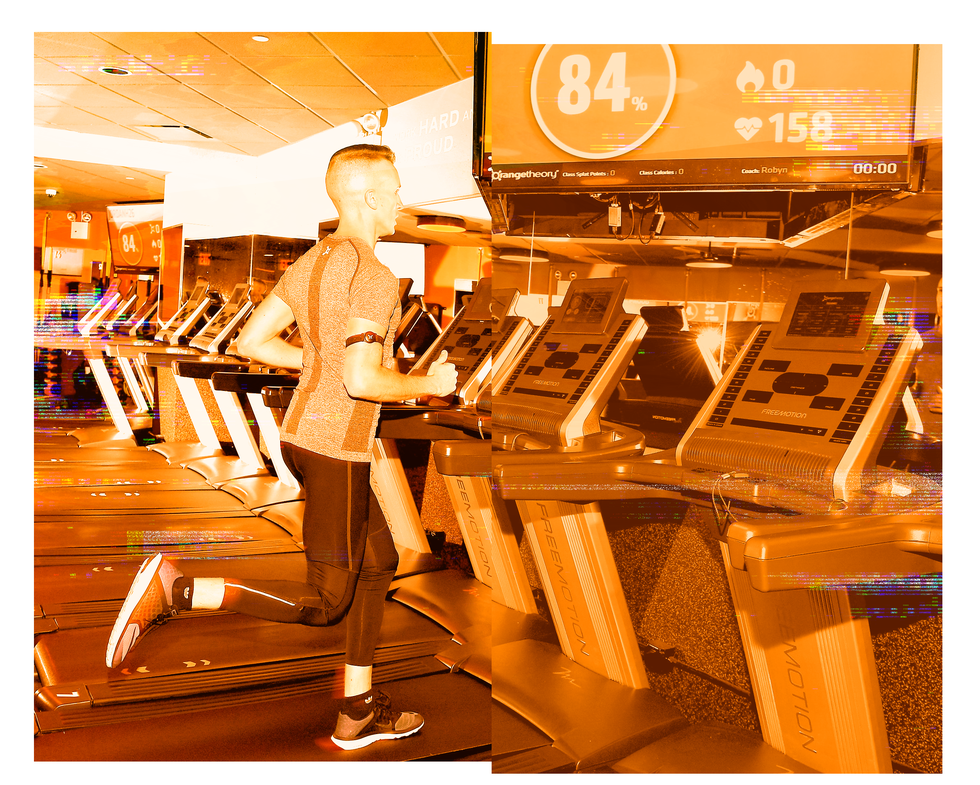

Abbate appreciated the team-like atmosphere and Orangetheory’s scientific promise: Push hard enough to spend at least 12 minutes of an hour-long workout in the intense orange or even red zone and you’ll trigger an “afterburn,” which keeps burning calories long after the workout ends. During class, such efforts are tracked in real time, as anyone wearing a heart-rate monitor during the workout will have their successes or failures displayed on a set of large screens.

By going four times a week, he lost 30 pounds in a year and improved every metric of his cardiovascular health, including his resting heart rate. “I’m in better shape than I’ve ever been in my life,” the now-63-year-old Abbate says. “I can keep up with 20-year-olds, and some of them say I’m an animal.”

Abbate is far from alone in his devotion to Orangetheory. Just before quarantine began, in January 2020, the company surpassed one million members and had 1,400 locations. While most Orangetheory gyms had to close temporarily during the outbreak, more than 90 percent are now open in some capacity. And while Gold’s Gym and 24 Hour Fitness have declared bankruptcy, Orangetheory has opened three dozen new U.S. outposts since August and hopes to triple that by the end of the year.

To survive and thrive amidst a worldwide shutdown makes the company an outlier in the fitness space. It’s even more impressive considering that the company’s take on afterburn, which played a huge part in its origin, name, and massive growth, has been recognized as overly simplistic, overly optimistic, and perhaps overstated.

In the past two years, Orangetheory has backed away from its original marketing strategy while refocusing on something that’s perhaps more powerful and that could carry the company beyond any of the customer confusion it helped create. As Abbate learned with each high five from fellow gymgoers, he hadn’t just joined a gym. He’d entered the bold new world of branded, hyperpositive, and communal fitness culture.

IN 2010, ten healthy young men at Appalachian State University each agreed to spend two full days inside a small room outfitted with a bed, toilet, and exercise bike. The room functioned as a metabolic chamber, a sealed space that controls temperature, humidity, and air flow while monitoring energy expenditure. At 11 a.m., each subject pedaled for 45 minutes at a vigorous pace that required them to reach a target exercise heart rate and stay there. On the first day, they ate only enough calories to equal what they had burned. During the second, they followed the same schedule but without the exercise bout.

Watching from a neighboring room was a team headed by David C. Nieman, Ph.D., the director of the school’s Human Performance Lab. The goal was to truly test the theory that vigorous exercise can lead to an elevated calorie burn for hours after because of a phenomenon called excess post-exercise oxygen consumption (EPOC). Or more colloquially, afterburn.

Nobel Prize winner Archibald V. Hill and fellow English physiologist Hartley Lupton are generally credited with discovering the concept in 1923. What they found is that if you work out hard, your body will be unable to take in enough air. Afterward, you’ll breathe in extra oxygen to make up for the deficit, a process that will burn calories. At least in theory. For the better part of a century, scientists continually debated the effect that afterburn might have on our bodies, without rigorously testing it.

The results of the 2010 study were “eye-opening,” says Amy Knab, Ph.D., who was then lead researcher on Nieman’s team. Overall, the subjects’ metabolic rate remained significantly above resting value for an average of roughly 14 hours after exercising. The workouts typically burned about 519 calories, while afterburn torched another 190. That’s a 37 percent bonus seemingly for going flat-out. “It was exciting to see, as we did not expect it to last that long,” she says.

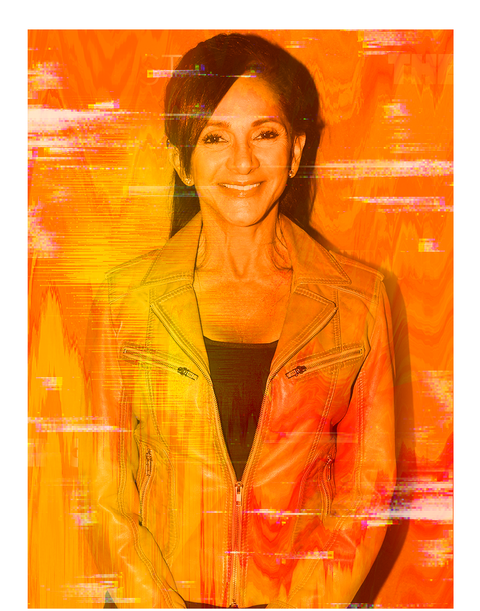

That same year, afterburn just so happened to become the main selling point at the first Orangetheory Fitness, a boutique fitness space cofounded by Ellen Latham. Latham, however, says she created her formula based more on general experience. “That science has been around since around the 1940s with interval training,” she says. “It’s nothing I invented. It’s just been around for ages.”

Latham was inspired to get into the fitness industry by her father, a phys-ed teacher and football coach in upstate New York. She got a bachelor’s degree in physical education and a master’s in exercise physiology before spending the next four decades managing spas, writing a newspaper fitness column, and teaching aerobics and Pilates.

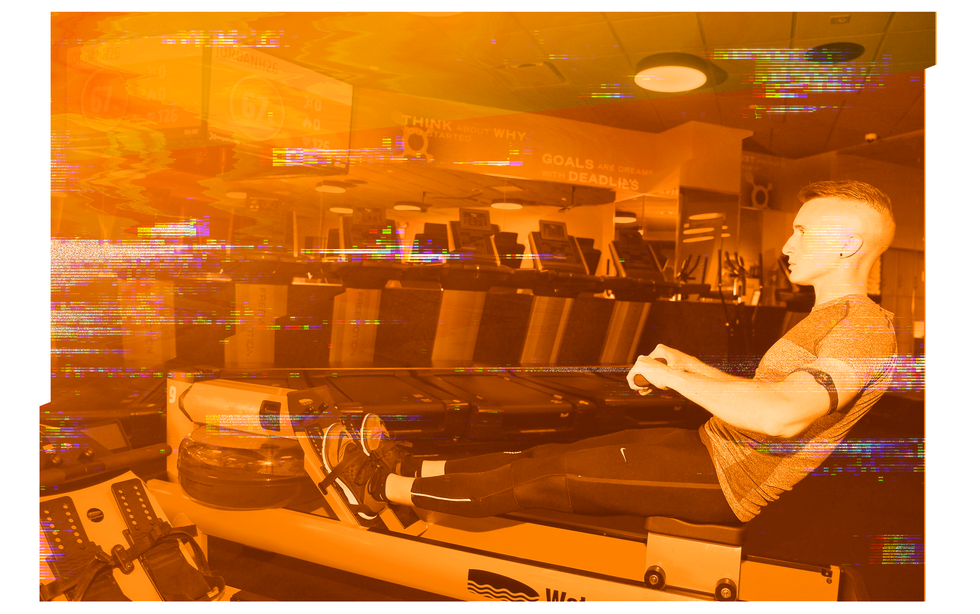

The exercises that Latham used for Orangetheory weren’t new, but she was among the first to combine things that were often not blended into the same workout, like rowers, treadmills, TRX suspension straps, medicine balls, rolling ab dollies, and BOSU balance trainers. People rotated between exercises every few minutes, and when they reached the cardio stations, they were expected to keep to a base pace between bursts of sprinting.

Her other secret was to gamify the experience with heart-rate monitors and catchy branding. Instead of a white-walled workout room, Orangetheory’s hubs offer a nightclub-like black theme with dramatic splashes of bright orange. Studios blare pop, hip-hop, rock, and dance music, while large screens allow coaches to demonstrate proper form and show everyone’s heart-rate level, like a leader board. For each minute you can stay in an elevated heart-rate zone (the orange and red zones), the system awards a “Splat Point,” a metric that Orangetheory regulars talk about like the spoils of battle.

Latham brought on partners Dave Long and Jerome Kern, who were known for their success at growing the Massage Envy empire before popularizing a national fleet of European Wax Centers. In just five years, Orangetheory opened 300 studios across the United States and globally from the Dominican Republic to Australia, and by 2018 the company had broken $1 billion in revenue. That fervor has carried over online, where 125,000 fans on Reddit swap stories and share their motivations.

Over the past year of uncertainty, Orangetheory has adapted perhaps as well as any exercise program. It added at-home workouts that kept the general public active, and it held classes outdoors or mandated extra safety protocols with reduced class sizes.

At some point, Latham realized that the concept of afterburn might be new to clients, so she worked hard to explain it. She created a chart that's been used by Orangetheory in recent years to compare the caloric burn of the average workout to that of her workout, with benefits that appeared to be two or three times greater. Clients would hit the orange zone at 84 percent of their maximum heart rate. After 12 minutes in that range, they would burn a bonus of 18 to 20 percent more calories than they’d used in the workout. The company claimed that this could continue over the course of up to 36 hours, a claim that still appears in a heart-rate tutorial on its website.

But Nieman disagrees with that math. “The Orangetheory concept, they kind of carried it out too far,” he says. He doesn’t believe that it’s possible to exercise for an hour and achieve a 36-hour afterburn. Or burn the proportion of calories that Orangetheory is suggesting given its workout. In short, the afterburn effect is real, but perhaps not as impressive as the company claims.

Men’s Health exercise-science advisor Brad Schoenfeld, Ph.D., C.S.C.S., is skeptical, too, and says taking some lab findings into the real world “hasn’t panned out.” In 2011, for instance, a study in the European Journal of Applied Physiology showed that afterburn could last for as many as 72 hours after a workout. But there were only eight subjects, and they were untrained, overweight, and doing intense resistance training that they weren’t used to, so the afterburn was likely the result of excessive muscle damage. For a workout like the one at Orangetheory, he says, new clients might achieve afterburn at first, but any benefits would likely trail off if the workout became a regular thing.

High-intensity interval training is obviously still a good way to burn calories quickly, strengthen your heart, and improve cardiovascular health. But Schoenfeld says the benefits of EPOC or afterburn following such routines are not “practically meaningful.” David Otey, C.S.C.S., an MH strength-training advisor, agrees, saying you might burn “a tiny percentage” of calories afterward, but it simply won’t lead to significant fat loss.

ORANGETHEORY'S HEADQUARTERS occupies a three-story rectangle of a structure not far off Interstate 95 in a well-manicured Boca Raton industrial park. It feels far more vibrant inside, with cubicles along an indoor exercise track on which “walking meetings” are held.

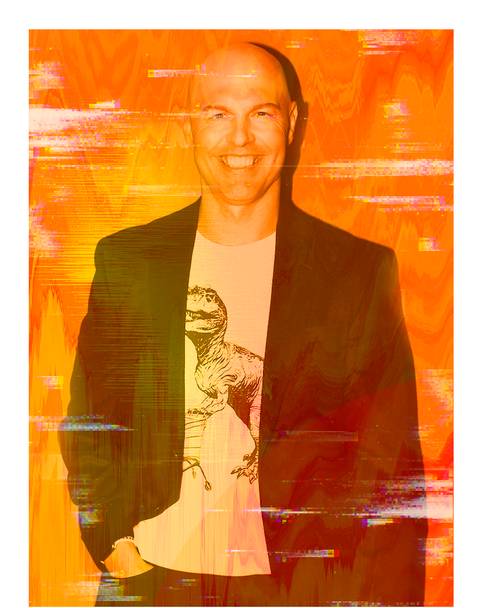

When I visited in January 2020, I toured the zen meditation room, featuring nap pods, a hot tub and sauna, and a massage area. In a glass-walled conference room, I met with cofounder and CEO Dave Long, who is bald, lean, and muscular. He sported Orangetheory-branded joggers and a moisture-wicking T-shirt and smiled broadly.

“The goal was, we want to give people the best workout in the most results-driven experience,” Long said. “We’re just going to focus on one thing and do it really well. And it has to be convenient.”

Today the company has an entire department called the Fitness Design Team, which is led by exercise physiologists dedicated to creating new workouts every day. For convenience, Orangetheory sells packages of classes for people who don’t want to commit to a monthly membership, something that has always plagued the fitness industry.

But the idea of creating a universal workout for everyone is too cookie-cutter for Schoenfeld, who says exercise ought to be tailored to your goals and abilities and what you personally need to stay healthy. “Trying a one-size-fits-all prescription is never ideal,” he says. A good workout should take into account specific injuries you may have, whether you’re doing the best exercises to challenge yourself, and how your coordination may suffer when trying a new move. All of these factors can also keep someone from elevating their heart rate enough to cash in on any theoretical afterburn.

There is, however, an undeniable benefit in the camaraderie of the workouts you’ll experience at Orangetheory, where being part of a large group can be a motivator. “People struggle doing isolated training, and the community helps them hit their goals,” Otey says.

When asked for men who have bought into the Orangetheory lifestyle, Long’s team connected me by conference call with a young fashion-industry manager living in New York City. He’d initially joined in 2016 and he liked the vibe, the science-backed promise, and the combination of cardio and strength training. By going five or six times a week, he surpassed 900 workouts in four years.

Many of those aspects appealed to me, too. In fact, I joined Orangetheory’s first studio not long after it opened, enjoyed learning new exercises in a supportive scene, and promptly started losing belly fat. I gave it up after a few months, mostly because it just seemed too expensive—it’s about $1,900 a year for an unlimited membership—especially for someone who considers cycling his main exercise.

During my visit to Orangetheory headquarters, I did the workout again for the first time in years in a class full of those who work in the building. At age 47, with a resting heart rate in the low 50s (thanks, cycling), I didn’t get out of the blue zone during the rowing and floor portions, even though I hit all the prescribed goals. That changed on the treadmill; since I haven’t been running lately, I stayed in the red zone nearly the entire time and finally started accumulating Splat Points. By the end, I came in near the top of the pack in my class, and it was hard not to walk out of there thinking about how I might do better or work harder the next time.

IN EARLY 2019, Orangetheory made a decision to shift away from its original marketing strategy emphasizing afterburn. Shortly after my visit to its headquarters, in early 2020, I noticed that the company had removed mention of 36-hour afterburn from its website’s “Fitness Science” page, which has also since been removed, and had replaced it with: “Orangetheory is based on the science of EPOC, excess post-exercise oxygen consumption.” (The company has since deleted that line, too.) A page titled “The Workout” includes broader statements about the benefits of the workout, although afterburn-science explainers can still be found on some international affiliate pages.

When asked about the initial change, Long said the company simply didn’t need to make afterburn the focus anymore. “Yeah, you know, I think it’s probably less relevant as a selling feature, but I think it’s extremely relevant in that it motivates people,” he said. To provide evidence for afterburn, the company offered Rachelle Acitelli Reed, its senior director of health science and research, who has a Ph.D. in exercise physiology. Reed joined Orangetheory in late 2019, recruited from Pure Barre, where she had been the head teacher at the studio in Athens, Georgia.

When asked to explain the company’s rationale for its 36-hour afterburn claim, she began with a simple analogy. “I like to explain it as kind of like a car. Even after you turn off a car, the engine stays warm.” Pressed for scientific research to support the 36-hour claim, Orangetheory’s PR firm emailed several studies and academic summaries dating back to 1985. Most of the research results varied widely in terms of the overall gain you can achieve with afterburn and how long it lasts, with one 2006 study in the Journal of Sports Science going so far as to suggest that, given the exercise stimuli required to elicit EPOC, its role as part of a successful weight-loss strategy for the untrained and sedentary is “generally unfounded.”

One of the studies directly supports the time effects that Orangetheory has touted. Published in the European Journal of Applied Physiology in 2002, the research indicates that afterburn may last as long as 48 hours. The author, Mark Schuenke, Ph.D., wrote the paper as his master’s thesis. Now a professor of biomedical sciences at the University of New England College of Osteopathic Medicine, Schuenke stands by the results of his study, which tested seven fellow students whom he pushed to “near nausea” levels for four circuits of bench presses, power cleans, and squats lasting just over a half hour with almost no rest time in between.

But Schuenke emphasized that his sample size was small. “More research is needed in order to truly confirm or deny the findings of my study,” he said, adding that Orangetheory “perhaps overstates” its 36-hour claim by basing it on nonreplicated research.

Pressed further, Reed said that based on additional research over the past decade on estimating EPOC, the company is now able to more accurately estimate afterburn impact on calorie expenditure and weight management. “Our science,” she says, “is ever-evolving.”

In an email, a PR company hired by Orangetheory then further clarified: “With advances in science fitness tracking and new studies surrounding HIIT workouts, along with bringing team members like Rachelle Reed on board, we felt it was best to adjust our claims so they are as accurate as possible for our members. After working with Reed and other members of the team, we felt that 24-hour afterburn is the most accurate figure we can give at the moment and wanted our brand messaging to reflect that.”

By keeping things so broad and vague, Orangetheory seems to be saying that, for one full day after you work out, well, something is happening. The statement added that the company will continue to “review and re-review our claims … to ensure accuracy and, most importantly, results.”

Does it matter if Orangetheory built an empire based on afterburn science that turned out to have questionable real-world results? Not to many members. In fact, those who occasionally question the methodology on Reddit receive plenty of responses implying that everybody knows EPOC is a myth, with one comment comparing the “fake” afterburn to learning that Santa doesn’t exist.

Abbate, who says his life was quite literally saved by Orangetheory, hasn’t slowed down, although his cardiologist recommended he stay away from gyms until he’s vaccinated. Throughout quarantine, he continued his exercise regimen through Orangetheory At Home, the online workouts the company began to offer after gyms were forced to close, offering a mix of cardio, core, and flexibility exercises. He says he’s still seeing improvements, dropping weight and body fat.

There’s no disputing that the cardio and strength training have helped his heart and overall fitness. Beyond that, Abbate doesn’t worry about the validity of the science. “The afterburn wasn’t what got me in the door originally,” he says. “I came because I needed a good workout, and it’s a good workout.”

That’s a great feeling, even if it’s hard to measure.