On a clear morning in early September 2019, a Russian diver bobs gently on the sparkling blue surface of the Mediterranean next to a support raft a mile off the shore of the French Riviera. At five feet eleven inches and nearly 190 pounds, Alexey “The Machine” Molchanov is sheathed in a golden wet suit, his feet snug in a matching golden monofin. He looks far larger than the lean safety divers that surround him in the water, waiting for the world’s reigning freediving champion to begin his descent.

Alexey wraps his fingers gently around a dive line descending from the floating platform beside him. Inhaling and exhaling slowly, he prepares for the single breath he will hold for the more than four minutes he plans to spend underwater. His target: a metal ring lined with white tags, suspended at the seemingly impossible to reach depth of 130 meters (about 427 feet). Round trip, that’s a journey equivalent to two and a half soccer fields. His goal is to grab a tag and then swim back to the surface before his lungs expire or his muscles give out—or both.

“Three minutes,” a judge shouts from the raft. With that, the countdown to Alexey’s gold-medal attempt at freediving’s premier open-water competition, the AIDA Depth World Championship, begins.

Competitive freedivers—those compelled to dive as deep, or as far, as possible on a single breath—have several ways in which they can distinguish themselves: with or without fins; with the assistance of the dive line; with weights; or even hitched to a heavy sled. Today’s event, known as “constant weight,” is Alexey’s specialty, and while most divers wear a weight belt to aid their descent, he relies solely on the weight of his monofin and powerful mermaid-style kick.

As the time ticks down, Alexey slips on his noseclip, which has been hanging cross-like around his neck, and adjusts its tiny metal arms over each nostril. With a minute to go, he begins packing—a breathing technique that looks like the desperate cheek flapping of a fish out of water—filling his lungs in spaces most of us will never put to use.

For the casual observer, freediving can seem like an unforgiving sport. It’s not uncommon for divers who push beyond their limits to suffer short blackouts from lack of oxygen, or blood in their lungs from the extreme pressure. In fact, just a couple days earlier, in another discipline that involved diving to more than 90 meters with no fins at all, Alexey blacked out briefly as he surfaced and was struck by a hypoxic fit, or loss of muscle control, known in the sport as “samba.”

The mishap didn’t discourage him from continuing. One of his favorite sayings is that these extreme competitions “are just a game for adults”—as though willfully ignoring the potential for disaster. Over the past decade, Alexey’s kept that mindset while continually stretching the peak of human performance. (Before fellow divers called him “The Machine,” he was known affectionately as “The Golden Retriever.”)

At age 34, he’s now ranked at the top of most of freediving’s open-water disciplines yet he still sets out every year to compete—if only against himself. During a competition held in the Bahamas in 2018, he pushed the world record in constant weight (held by none other than, you guessed it, Alexey Molchanov) from 129 meters to 130 meters. The depth goal today is the same, but the water down below is roughly 20 degrees colder than in the Bahamas, making this a much more demanding dive.

When the judge gives the signal, Alexey waits ten seconds and then dips his body, hovering on the surface for a moment before flipping headfirst into a duck dive, his monofin hitting the water behind him with a single delicate slap. The dive may test his physical limit, but he’s chasing something more than records. By continuing to venture as deep as possible, he’s able explore more of a majestic otherworldly realm. For most of his life, figuring out how such submersions affected people was a family quest. Until it led to a loss he never expected, one that has only pushed him to go deeper.

Alexey’s parents loved the water before they loved each other. Both children of the Cold War, Natalia and Oleg met during swimming meets in their teens. Later, after they were married, they moved to the city of Volgograd in the south of Russia along the Volga River to start a family.

Before the age of five, Alexey made local headlines for his performance in the 500-meter backstroke. Soon he was a champion in freestyle and butterfly, too. On family vacations at the Black Sea, he donned archaic diving gear that towered over his frame and began to explore the deep.

As Alexey neared high school, his parents separated, but his mother made sure his training continued uninterrupted. He was accepted into the Raduga Swimming Sports School of Olympic Reserve, a specialized school for young Russians with gold-medal dreams. Then in 2002, Natalia, 40, told Alexey about a new sport that she had discovered that combined their collective interests and skills: swimming, competition, the sea. The sport was called freediving.

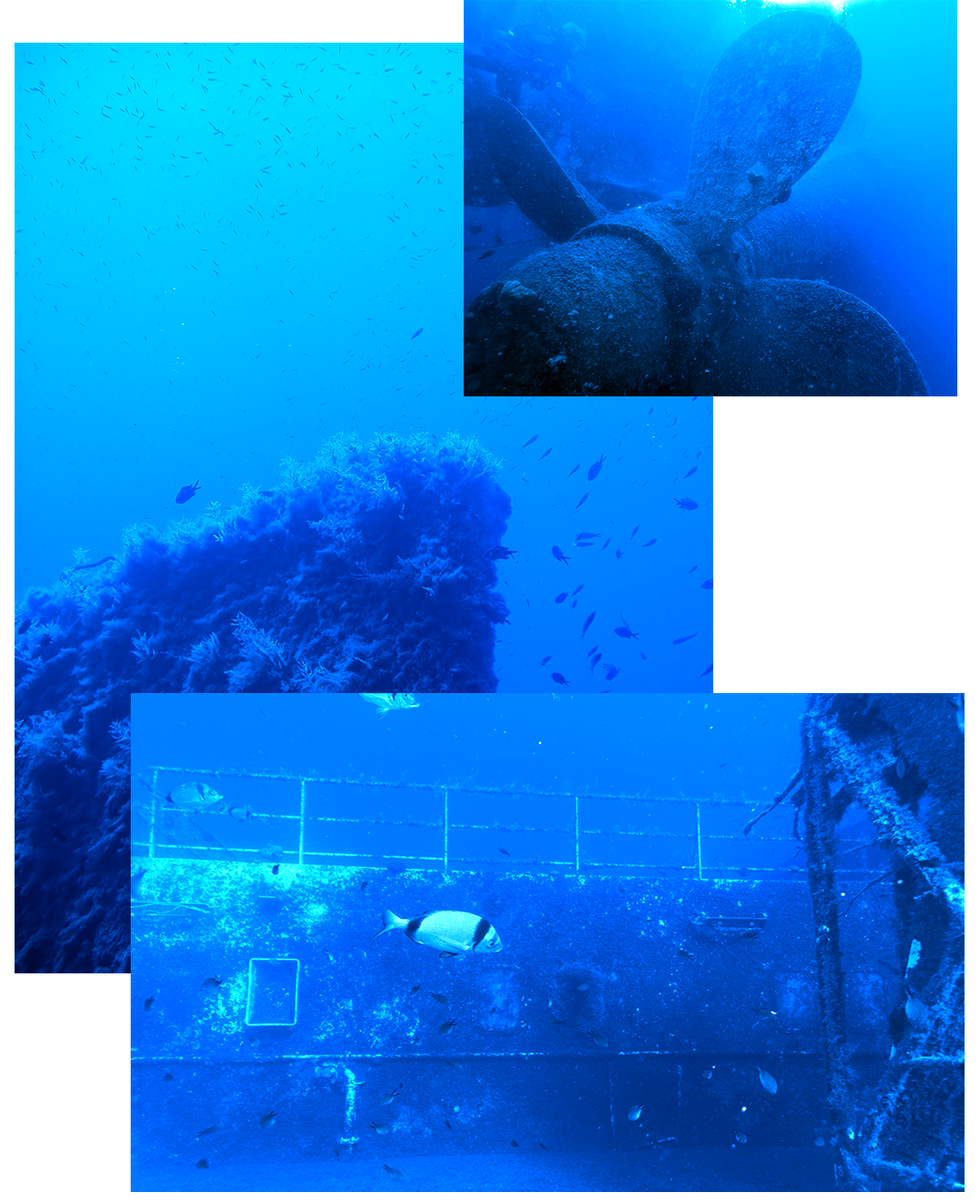

In April 2004, Alexey entered his first freediving competition and won, setting the Russian national record in a back-and-forth pool discipline called “dynamic” at 158 meters. That same year, he traveled to Cyprus to watch Natalia in an open-water competition. There, he ventured a hundred feet down through the royal-blue water to examine the Zenobia, a famous wreck with propeller blades longer than a man, entirely on one breath hold. “I was following her and she took me in this exciting world, which looked like a dream,” he says.

Holding your breath to dive deep into the sea is something that humans have been doing for thousands of years. The story of freediving as a competitive sport, however, starts in 1949 when Hungarian-born Italian air force captain Raimondo Bucher dove 100 feet to reach the seabed in the Gulf of Naples to win a bet against fellow diver Ennio Falco. Bucher astounded those who had been convinced that the water’s pressure would surely crush him to death.

By the time AIDA—the International Association for the Development of Apnea—was founded in the early ’90s in southern France, pioneers such as America’s Bob Croft, Italy’s Enzo Majorca, and France’s Jacques Mayol had pushed depth records to over 100 meters. The sport even got the Hollywood treatment with Luc Besson’s The Big Blue in 1988.

These early freedivers also served as guinea pigs to the still-developing study of underwater human physiology. Researchers found, for instance, that Croft’s body adapted to conserve more oxygen underwater and that Mayol’s heartbeat decreased from 60 beats per minute to 27 during his dives, a phenomenon discovered previously in Tibetan monks in meditation.

Studies like these ultimately fueled our understanding of the mammalian dive reflex in humans. This physiological reaction, which affects all aquatic mammals, is triggered by immersion in water—particularly, of one’s face—and apnea, the holding of one’s breath. The reflex allows divers’ bodies to adapt to extreme depths, if they can learn to harness it.

For the first 20 meters below the surface of the Mediterranean, Alexey works hard. He fights against his body’s buoyancy with a steady pulse of dolphin kicks. His arms are extended and snug against his ears in streamline. Eyes closed, he wears no goggles, entering the depths blind to his surroundings. At 20 meters below, he floats his arms down to his sides as, under the influence of the sea’s barometric pressure, his lungs compress to a third of their surface volume. Now negatively buoyant, he enters the opening stages of freefall and starts to sink. The fight, for the moment, is over.

Alexey is moving at roughly one meter per second. He need only give himself a slight boost, a kick every ten meters—which he does with an uncanny accuracy, on autopilot—to maintain his speed. This is Alexey at his most beautiful: smooth, fluid, at peace. Mid-metamorphosis, he glides as his body mutates, his stomach hollowing out as the air in his lungs divides into still-smaller fractions.

Clipped securely to the dive line by a cord attached to his wet suit, he focuses not on navigation but rather diligence. The main task: the transfer of air between his mouth and his sinuses to equalize his body’s cavities in the hopes of avoiding a squeeze, a pressure injury to the lungs, ears, or sinuses. As he does so, his mind is held in a rigid yet gentle state of extreme calm, keeping at bay the syrupy embrace of nitrogen narcosis, an effect of nitrogen saturation that can cause panic or giddiness or both, depending on the dive and the day. The rapture of the great depths, Jacques Cousteau called it, or, in scuba talk, getting narc’d.

Within a year of discovering freediving, Natalia had transformed herself into a self-taught expert in the sport, with several national and a few world records to her name. And Alexey was close on her heels.

Over the next decade, the Molchanovs rose quickly through the ranks of competitive freedivers, trading national records for world records, world records for new world records. By 2005, Natalia was living in Moscow, leading the Russian Freediving Federation and running a freediving program at a local university. Alexey had moved there too in pursuit of a software-engineering degree. With a training course that Natalia developed, they would go on to certify more than 100 freediving instructors.

Natalia also dedicated herself to researching the potential effects and benefits of the sport. “She would give a lot of love, always,” Alexey says. “She was always taking time to talk to people, to explain, to help with advice, about anything.”

In 2009, in the water off of Sharm el Sheikh, Egypt, in the Red Sea, Natalia became the first woman to pass 100 meters, diving to 101 meters in constant weight. Three years later, on her 50th birthday, she broke the world record in a no-fins dive to 66 meters. The next year, she smashed a half dozen more world records. “Many people, when they reach 50, they think life is over,” she told the writer Adam Skolnick for his book One Breath: Freediving, Death, and the Quest to Shatter Human Limits. “I want to show them, there is more they can do.”

Deep dives always involve risk. But while dozens of freedivers, including spear fishermen and recreational divers, die each year, among competitive freedivers, fatalities are extremely rare. The tragic 2013 death of Nick Mevoli, the subject of One Breath, remains the sport’s first and only in-competition fatality.

Close calls, however, are more common. Yet Natalia and Alexey grew comfortable with the trade-off. The same year that Mevoli died, Alexey went to Greece for a then–world record attempt of 128 meters in constant weight. He had recently had a cold—a punch to the sinuses—but he was feeling confident and strong. On the way up, however, at a depth of 110 meters, he was struck by a reverse block—an injury to the middle ear that scrambles a diver’s spatial awareness—and became disoriented.

At 30 meters, he passed out, and a safety diver, the accomplished Irish freediver Stephan Keenan, had to drag him to the surface. Such deep-water blackouts can be catastrophic, but Alexey escaped the whole ordeal with no more than a severely squeezed lung, which left him coughing up blood. In One Breath, Keenan recounted how, afterward, Alexey thanked him but downplayed the accident, as if he were “in total denial.” Six days later, he got back in the water and set his world record. “It just shows his resilience and determination,” said Keenan, “and the psychology of the strongest freediver.”

On August 2, 2015, just one month before the annual AIDA Depth World Championship, Natalia was in the water off Formentera, an island near the Spanish archipelago that includes Ibiza, giving a private dive lesson to two students. During the lesson, the students watched as she disappeared below the water in a dive later estimated to have been no more than 100 feet in depth. It should have been routine for the Russian champion—at 53, she was now the most decorated athlete in freediving history, with 41 world records and 23 world championship titles. But Natalia never resurfaced.

When Alexey received the call, he flew to Ibiza and received the reports from the search party out on the water. But he knew there was little hope: Going missing at sea is almost always a death sentence. There would never be an official statement, a final word on what had happened to Natalia—many speculated a powerful current or a freak head injury—but Alexey felt one sickening certainty. “If I had been there,” he said, years after his mother’s disappearance, on a podcast called Freedive Café, “most likely, nothing would have happened.”

At 129 meters below, Alexey feels for the marker that will indicate he’s reached his depth. Below this is the metal ring with its white tags, gently waving in the water like a ghostly mobile. He grabs one and turns skyward. Unlike the journey downward, a task that eases with depth, climbing out of this high-pressure zone is extremely demanding, as divers fight against their negative buoyancy with bodies shot through with lactic acid and carbon dioxide.

Rather than think about if he’ll make it or not, he trusts his body’s muscle memory to pick up the slack. As he once put it: “You need to be just performing. You need to clear your mind and you need to focus on the things you know how to do.” As he rises, Alexey switches back to manual, oscillating his body and fin in varying rhythms, as if responding to the water’s every stimulus.

When the search was called off, Alexey flew to Egypt, to the waters of the Red Sea, his and his mother’s preferred practice grounds, and began to train with teammates from the Russian national team. A month later, he went forward with his plan to compete at the championship.

He went home with two gold medals. In 2016, he pushed the constant-weight depth to 129 meters and then, in 2018, to 130. He set the world record in another discipline, called free immersion, also in 2018, and early in 2019 he set it in yet another, bifins. In 2020, he pushed the bifins depth still further and earned a Guinness World Record for longest recorded dive—nearly 600 feet—under ice. Next up, in mid-March, he will attempt to dive under the frozen crust of Russia’s Lake Baikal, the world’s deepest lake, to attempt yet another Guinness World Record.

Before his mother’s disappearance, Alexey had been a fierce competitor and a promising young diver; after, he’s become the world’s best. He’s become something else too: a kind of millennial evangelist for his sport. On Instagram, where he has 111,000 followers, his posts demystify and destigmatize freediving through stunning underwater vistas, free advice, and quippy captions. (“Work life balance” he writes, under a photo of him in scrubs, cradling both his newborn son and his cell phone.)

This is one way for him to continue to share his mother’s philosophies on diving, but he is also developing his own. “You can have a very unique experience underwater, like that you are very small, that the ocean around is very big,” he says. “And it allows you to rethink your scale, how small you are in this universe.”

As anxiety-provoking as the sport may seem to the uninitiated, freediving has been shown to reduce anxiety and help with depression and trauma. This recent research has helped Alexey understand why he still felt so inexorably pulled toward the water after his mother’s disappearance. Put simply, it was—between the sensory deprivation, the elemental immersion, and the simultaneous control and surrender—an escape. His own form of therapy and his way to process the loss. “Intellectually,” he says, “I was realizing what I need to do, what I have to do, to continue her legacy.”

After Natalia’s disappearance, Alexey continued running the gear side of Molchanovs, the freediving business they had started together. In 2018, he and two other big names in freediving, Adam Stern and Chris Kim, who cofounded Molchanovs, decided to relaunch Natalia’s training protocols as the Molchanov Freediving Education system and to make it available in English. Through its tiered courses, Molchanovs is similar to other established freediving programs: You start at the basics and work your way up to longer breath holds and deeper depths. Plus, those who wish to can become educators themselves. So far, they’ve certified more than 500 new instructors.

With training, competitions, his business ventures, and a growing family, Alexey shares the same stress as any top athlete. But in the time I spent with him, he was always stopping to play tricks on his fellow competitors, splash around in the shallows, or enjoy copious amounts of oysters. “He doesn’t reach high levels of performance by being this hyperintense person,” Kim says. “He reaches it by being a hyperfocused person, who is also very relaxed.”

Stern chalks this up to Alexey’s ability to keep the intensity of competitions separate from the rest. “I had been told that he was just a machine of a person, and as a diver he is,” he says. “But as a person, he’s a big cuddly teddy bear.”

Twenty meters from the surface, the buoyancy catches Alexey, and his legs calm. It is just one, two kicks and then his arm is up, on the line, above water. He completes the necessary surface protocol to prove his body and brain are functioning correctly: the removal of his clip, an “okay” sign with his hand, and then, between deep, rattling breaths, the verbal, “I’m okay.”

Once he dislodges the white tag from where he has tucked it away, in his hood, several officials floating in the water in front of him grin to each other before flashing the white card. Alexey’s protocol has been approved; his dive is valid. The crowd on the raft erupts in applause. He’s matched his record; the gold medal is his.

By midafternoon, he’s back on shore, sitting at a table at the championship’s open-air cafeteria with his shoulders slightly hunched, as they usually are when he is out of the water. He’s traded his wet suit for the Russian team T-shirt, moisture-wicking navy shorts, and white Croc sandals. Everyone has been talking, all day, about his dive. Now, in this rare moment of free time, he wants to see what all the fuss was about. So with the day’s livestream queued, his iPhone propped up against his water bottle, he watches.

When the dive is done, he presses pause. Smiling, he says that it is strange to see the difference between what one thinks one looks like in one’s head when one dives and what one actually looks like.

“What do you look like in your head?” I ask.

“Better,” he says, with a laugh.

When surface life fades away anything seems within reach.

Sami Emory is a writer from Northern California, based in Berlin. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, The Baffler, Wired UK, Gossamer, and elsewhere.