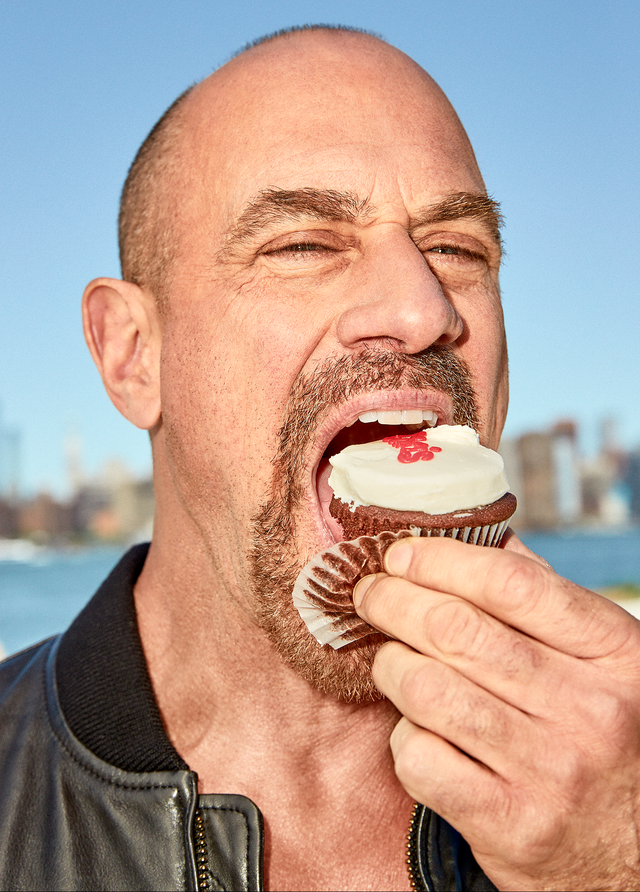

THEY ARE WALKING with their border terrier along the Hudson on the west side of Manhattan. It’s a late-spring morning, and small swells of river are flicking at the wooden posts poking out of the water, ghosts of an expired pier. Christopher Meloni asks Sherman, his wife of 26 years, if they’ve gotten a bid on demolition—they just purchased an entire floor of a co-op in the West Village, and Sherman, an artist and former production designer, is going to lead the renovation of the investment property.

Meloni tells her he’s going to let Scotty off leash, which Sherman warns is against park rules. “He’ll be fine,” Meloni says, unclipping the dog and turning back to the reno updates. No one recognizes the actor, a rare occurrence lately. After a few minutes, they wonder: Where is Scotty? Meloni whistles for him, lowering his NYPD hat and turning until he sees the wiry little dog in the sunlight, sniffing a full plastic bag on the waterline. “Get away from that!” he says, annoyed. “You know, these fucking guys throw garbage away, and it just floats up on our shores.” Sherman grabs Meloni’s extravagantly muscled bicep. “I don’t think that’s trash,” she says. Meloni finally understands that the bag is actually a body bag: There’s been a grisly, perverted murder. “Call 911,” Meloni says over his shoulder, running toward what he now realizes are the remnants of a victim. “Don’t go too close to the body!” Sherman calls out while dialing. “It’s a crime scene.”

“I know it’s a crime scene!” Meloni shouts. “I do this for a living!”

Chun-chun.

That is how Meloni merrily turns the story of a placid morning into the cold open of an episode of Law & Order: SVU, the corner of the Dick Wolf multiverse in which he spent 12 years bashing perps. He played Detective Elliot Stabler, who retired from the force in 2011 due to an offscreen contract dispute with NBC. Meloni spins his tale of corpse finding from the 26th floor of a luxury high-rise purchased with the money that enticed him to return to Law & Order in his own spin-off, Organized Crime. Stabler is now in his mid-50s and coming into, Meloni says, “a world he doesn’t understand. You know, you’re a white cop of a certain age, you’re not allowed to do a lot of things, and you’re being challenged on your bona fides on both sides. How woke are you? And how much of a man are you?”

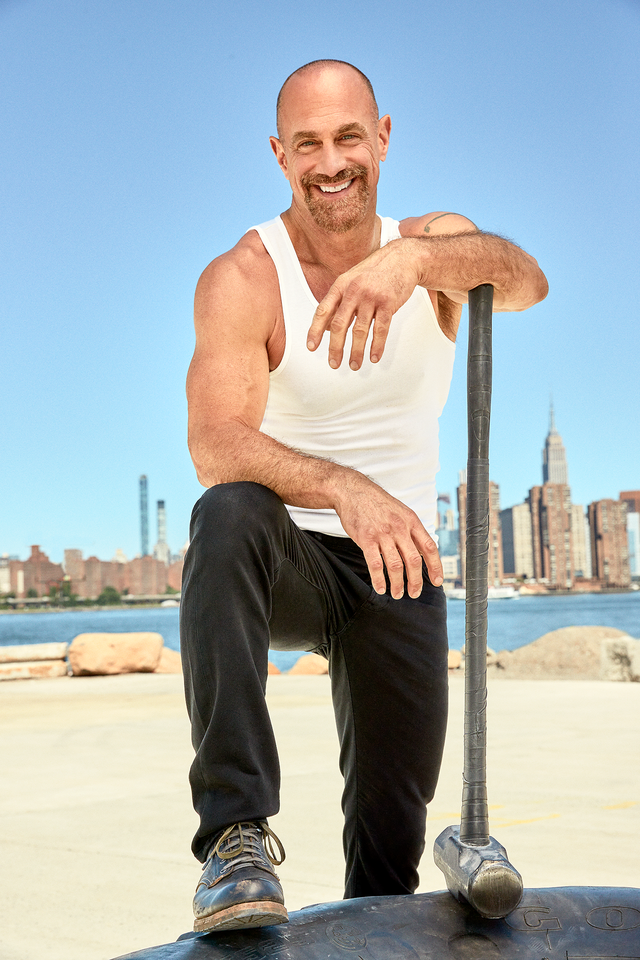

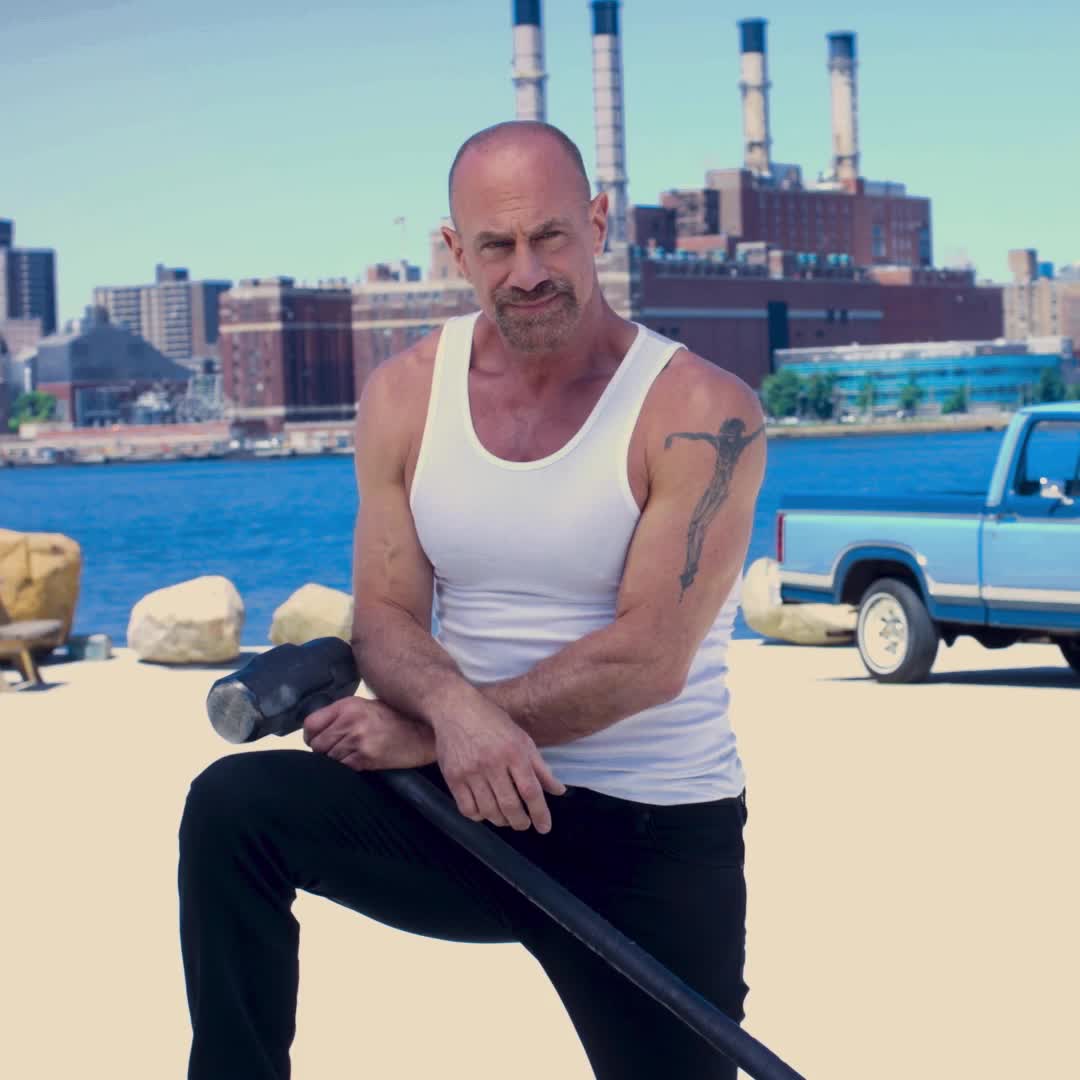

One could also ask these questions of Christopher Meloni. Yet this past spring, Americans seemed to spontaneously and simultaneously cathect on this white man of a certain age who plays a cop. Organized Crime debuted in April, followed a week later by an on-set photo posted to a neighborhood Facebook group that depicted Meloni’s butt girth appearing to rival Kim Kardashian’s, and then, a few days after that, a tweet by Queen Cher:

“Zaddy!” the Internet cried. And Zaddy Meloni welcomed his new acolytes onto his thickly quaded lap. When I tell him he’s having a cultural moment, he says, accurately, “My ass is.” And Meloni, with his butch blend of off-color bluntness and gleeful mugging, is enjoying the high. “It’s cool as shit,” he says of having a renaissance in the back third of his life, sipping espresso out of a mug with his face printed on it. “The aspect of age comes into play as far as the cover of [this magazine] and how I feel about it. A friend of mine said, ‘Did you ever think in a million years you’d be on the cover of Men’s Health?’ I said, ‘Certainly not at age 60.’ ” In other words, if Meloni and his melons were going to happen, they should have happened already. So why does America want him to be its Zaddy now?

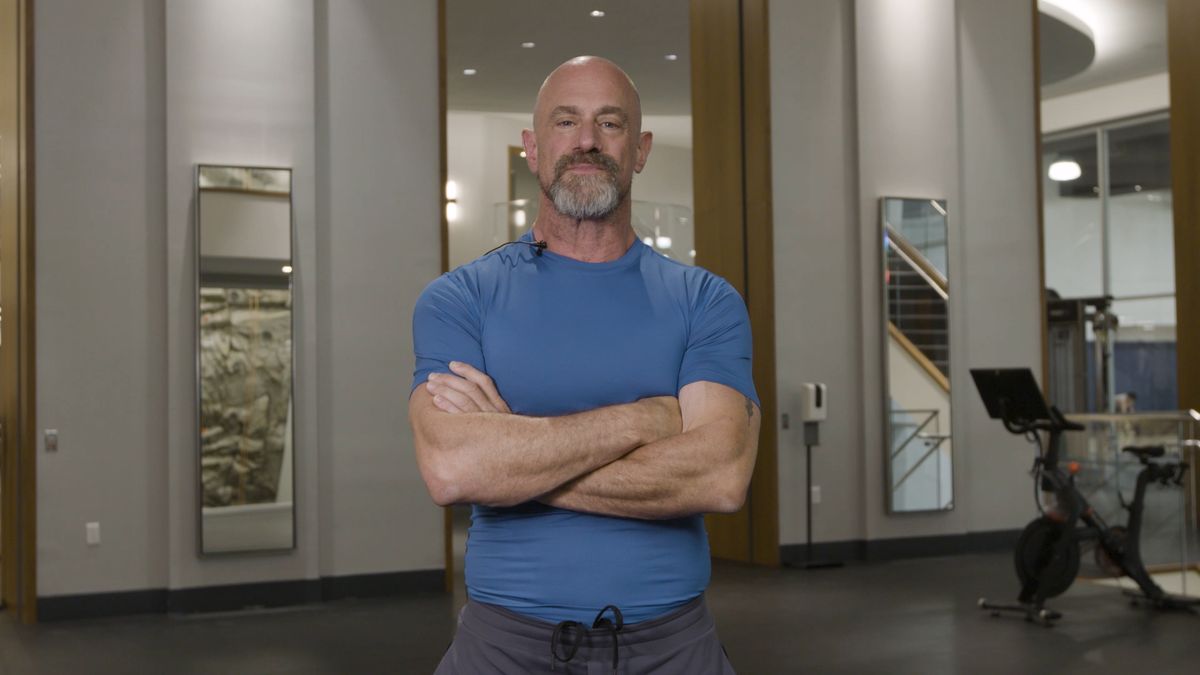

MELONI HATES BULLSHIT. Can’t stand it. When I show up at his building ten minutes early—thinking I’d wait while setting up in the gym where we are supposed to do a punishing workout together—the doorman says Meloni wants me to meet him in his apartment, where he is scowling and rubbing out knots with a Back Buddy massager. “I’m edgy,” he says by way of greeting. He’s on hour 12 of an intermittent fast when we head down to the building’s gym to grunt through 80 minutes of box jumps, pullups—Meloni does 25 while I manage zero, which he nonverbally attributes to a total lack of lats and rhomboids with a grim tap to the outside of my shoulder blade—and something called “the saw,” a move as unpleasant as it sounds. I am informed that this is a light workout. Meloni is balletic in this beastly show of force, though there’s a cost. “You have trauma,” he says, “and your tissue doesn’t go back to normal. Then you have a scar, so you don’t have flexibility of the tissue to move. The pliability of it is compromised. So I’m compromised. I feel my compromisation.”

After the workout and an egg-white omelet with cheese that has raised Meloni’s blood sugar to a level at which socializing isn’t so burdensome, I propose we stay in the no-bullshit zone. Meloni agrees, though throughout the interview it becomes clear I didn’t need to make the request. During our time together, he will animatedly point out that I’ve spat on him, and after I explain what a recurring dream is with an example of one of my own, he says, “Can I be no bullshit? Let’s not talk about dreams.”

Meloni grew up in a home thick with silence and bullshit. His parents were Catholic, and every Sunday he and his brother and sister would attend Mass with them. “Going to church was close to death,” he says. “Saturday afternoon would roll around, and my weekend was over. That’s how much I dreaded going to church.” It was the lack of honesty and clarity that bothered Meloni so much. “Who exactly is the big dog?” he says of the moment of his disillusionment. “I got a Father, I got a Son, I got a Holy Ghost. I remember asking a nun about Jesus and God, and she couldn’t give an answer. I was about nine, maybe 11. I was like, ‘You know, I feel like I’m done.’ ”

At home, things weren’t any more transparent. “Living in that house was like living in a dark cloud,” Meloni says. “They were so quiet and so reserved, but you feel it.” Or at least he did—no one else in the family seemed bothered by the silent tension. “I just remember always looking around, like, ‘Am I fucking crazy?’ ” No, Meloni decided. He was acknowledging reality. “Get the fuck out of here,” he says he thought of the entire situation. “I could feel it.” It is still there, compromising him. “The trauma of childhood is real,” Meloni says. “And I carry that with me.”

Meloni graduated from the University of Colorado Boulder with a degree in history, focusing on contemporary U. S. diplomacy and communism. Not long after he graduated, he says, “the Berlin Wall fell, so it was all a moot point.” Obsolete degree in hand, he went to New York to train at an acting studio, then embarked on more than a decade of mostly unsuccessful auditions. When they would go badly—which was almost every time—Meloni would stand in front of a mirror in the apartment he shared with three others and scream at himself: “What the fuck are you doing? You get the opportunity to be in the room to take this job, and this is what you do? This is the best? That’s what you did? You sucked!” He demanded he answer for his failure. “What are you doing?” he shouted at the person he knew could do this but just kept blowing it. “What are you doing?”

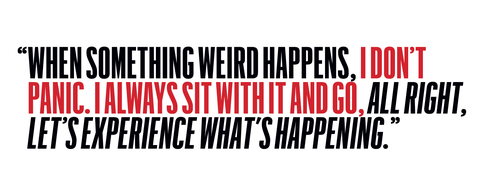

Then, suddenly, what Meloni was doing started working. In 1997, he got a role on one of HBO’s first prestige dramas, Oz, as inmate Chris Keller. A year later, he debuted on SVU. Just after taking on the leading role, Meloni woke up in the middle of the night trembling uncontrollably. He got out of bed so that he wouldn’t wake Sherman during what he thought might be his dying moments. “When something weird and out of the norm happens, I don’t panic,” Meloni says. “I always sit with it and go, All right, let’s experience what’s happening, because getting tenser is not going to help the situation.” When he realized it was merely a deluge of anxiety, he let it subside and went back to sleep. This occurred two more times over the next few months. (“Is this ‘Chris Meloni’s unstable’?” he asks about the thesis of this article in his brusque deadpan. “Is this the fucking theme we’re going with? Because I’m not going to stand for it.”)

Meloni was being crushed by the success he sought, a dog getting run over by a car he’d managed to catch. “When my career started to happen, I could feel it,” he says of the powerful position he’s attained again. “But I didn’t want to trust it, because I had struggled for so long—or at least it felt like I’d struggled for so long—and I didn’t want it to go away. I don’t know how many people get this opportunity to dream a dream and have it come to fruition. Because everyone does the first part, but to have it come to fruition then starts a whole other journey of Now what? And What is this? And How do you manage?” Meloni knows this is a top-shelf problem. “This doesn’t fall under the category of burden or anything like that,” he says. “It’s just a new world. You’re so used to the old way of: I have to keep this mindset and I’ll just dream a dream. But if the dream actually happens, then you’re like, Okay, now we have to manage the dream. We have to . . . what do we do, actually?”

Around the time he was shaking himself awake, Meloni was called back to the church. It was Christmas Eve, and he and Sherman had just moved into a SoHo loft and were about to start a family. His career was exploding, and he was wondering what that meant for him. While he was out for a walk, it began to snow, just enough for the sidewalk to glitter under the streetlights. Meloni remembers thinking, “Oh my God, if this is not a sign to come back to the fold. . . . I was legitimately pensive, feeling the moment. I was just overwhelmed with the love, the beauty of it, the spirituality of it, the potential of it. I remember almost floating to Mass.” The church was packed, and Meloni joined the flock. The father came out, and everyone stood, ready to receive the Word. And lo: “This guy could not have been more bored, more uninvested, more by rote,” Meloni says. “He might as well have been reading the phone book. And I went, ‘There you go. You’re just as tired as you were when I left you.’ ” Meloni would have to find his own answers.

LAW & ORDER: ORGANIZED CRIME has been a more successful return to a sacred institution. Meloni left in the first place when contract negotiations broke down. He says he told NBC, “Well, if it’s this”—meaning this amount of money—“then this is the way to go around so you don’t have to pay this”—meaning this larger amount of money that Meloni wanted. He got creative. “My thought was: Instead of 22 episodes, bring me back for nine episodes, or bring me back for 18 episodes. They literally came to me on a Thursday night and said, ‘This is the deal. We want the answer by tomorrow. It’s our way or no way.’ ” And that, to Meloni, was some bullshit. He says he told them, “I don’t want to fuck around with you guys. This is what I want. If you can’t do it, that’s fine. Let’s figure out my exit.” (That may be the downside of the “no bullshit” dictum. Despite his decades at NBC, Meloni says he has few friends there. “I’m just not a showbiz guy,” he says, crediting that to being “horrible” at schmoozing.)

Meloni spent a few of his post-exit years living in L. A. at the base of Runyon Canyon. He departed the stolid world of procedurals, bringing the weirdness that emanates from him in person onto the screen, as the fridge-humping camp-cafeteria chef in Wet Hot American Summer and as the star of a two-season Syfy show called Happy!, which he tries to entice me to watch by screening a scene in which his character has pink cartoon diarrhea. He had a minor but excellent part as the stepfather in Marielle Heller’s directorial debut, The Diary of a Teenage Girl. Heller says she initially found him “intimidating”: “I remember my first phone call with Chris, and thinking, God, he’s so intense and gruff.” During production, she discovered the sillier side of Meloni. “There was a moment when we were filming and this fan came up to him and asked to take a picture of his butt,” Heller says. “He posed in a funny way, then turned to me with this sly smile and said, ‘There’s kind of a thing about my butt. People are really into it.’ ” Meloni was in small projects for which, he says, “you’re a little sapling trying to find the light.” But what he calls the “800-pound gorilla” of Law & Order kept stomping through.

Then in February 2020, Dick Wolf summoned Meloni to Burbank and proposed he return as Elliot Stabler on a series built around the character, who is avenging his wife’s murder by the Mafia. Wolf says he’d wanted to reunite with Meloni “since the day he left” Law & Order, and he finally got his wish.

It worked. Organized Crime is the 12th most watched TV show in America and the fifth most watched scripted series. Meloni owns two large homes in Manhattan and a lake house where he can water-ski. There’s a better-than-decent chance his ass is trending right now.

People missed Meloni’s Stabler—his banter with Mariska Hargitay’s Olivia Benson, which always stayed respectful and nonharassing; the fact that he was obviously capable of hurting others but only ever did so when they were bad, bad people; the well-meaning paternalism that made you feel like “If we’re stuck with the patriarchy, at least this powerful white man has good intentions.” Organized Crime’s showrunner, Ilene Chaiken, who also created The L Word, says, “He’s a good one. If we have to have a daddy, let it be him.”

Meloni seems to share some of Stabler’s core qualities, or at least grapple with them. When his character in The Diary of a Teenage Girl was rewritten to have an affair with his stepdaughter’s 15-year-old friend, he called Sherman to make sure their daughter would be comfortable with it being depicted onscreen. He’s rabidly protective of his family—the only times he goes off the record during our conversation are when we talk about them. And the sole time Meloni refuses to answer a question is when it seems like they are the answer: When I ask if he’ll tell me why he went back to Law & Order, Meloni oscillates his head along the no axis and says, “It felt good to have to make that decision—which was a big yes-or-no decision—with a sense of clarity and a sense of certain things being correct.”

THERE ARE MANY paintings in Meloni’s home, but two stand out. They are nearly life-size portraits of Meloni and Sherman, rendered by artist Andrew Myers on what appear to be gigantic pieces of ripped-out binder paper. Around the figure of Meloni are assessments, like what you might see in the comments section of an elementary-school report card, which the artist wrote down after talking to him. Meloni, like Elliot Stabler, is not much for self-reflection; when I ask him how he feels after our workout, he has a hard time answering. “It’s very strange,” he says after a pause so long I assumed he either hadn’t heard or was ignoring the question. “I never talk [about] or discuss it.” Exercise, he says, is “therapy, church, meditation, and a kind of personal reengagement where the brain and the body get to talk to one another”—apparently so he doesn’t have to speak about it himself. Still, Meloni found being interviewed by the artist therapeutic. “[Intense]ly funny,” the painting says. “What/who are you protecting?” “You seem to be questioning the questions!?”

At the top of the painting is a letter grade, which Meloni assigned himself. B+. Why didn’t he give himself an A? “Because I don’t know what an A looks like,” he says.

But Meloni no longer wakes up in the middle of the night terrified by the thought of failing. If things fall apart—if Organized Crime eventually gets canceled (it was renewed for season 2) or he comes to another impasse with NBC or, God forbid, his glutes pancake—it will be okay. “This time around with the Law & Order ride, I’m not stressed by: Will it go well? Will it not go well? Not that I know how it’s going to go. Just that, eh, just ride. Just do, just be.” Because Meloni knows now what he didn’t know the first time: “There are bigger things, more important things. I know how important this is to me, but I have a clearer vision of life. I know a little more about love. I know a little more about real pain. I know about joy. I know better management skills. As you go through life, you get a clearer understanding of things, of your holes and of your gifts.”

Meloni finally asks: What is a “Zaddy,” exactly? “I just thought it was a cutie thing,” he says, as adorable as a hulking 195-pound man can be. I explain that a Zaddy is a distinguished vintage. “Daddy plus?” he asks. “Daddy platinum?” Then he gets why he couldn’t be our Zaddy before now. “It’s reserved for an older gentleman,” Meloni says in wonder, his cobalt eyes widening. This moment couldn’t have happened until now, because Meloni wasn’t yet who he is now. “How much am I allowed to taste of this fruit?” he says, intoning the existential question of success with the confidence of someone who has very literally restricted his fructose consumption to achieve the tuchus we extol. “How much am I allowed to enjoy this?”

While we look out over the Hudson and Meloni eats peanut butter, we talk about the flow state—how sometimes, like right now for him, you hit all the green lights. When I tell him I’ve been killing flies with incredible accuracy lately, he says, “I catch flies with my ass cheeks, like a Venus flytrap.” He giggles wildly. “I’m clever with my ass cheeks!” he says, cackling. Moments later, a fly lands on the table. Meloni raises his hands. There’s a clap, then silence, and Meloni is smiling, once again looking down at a dead body.

This story first appeared in the September 2021 issue of Men's Health.

Anna Peele is a culture writer and editor who has written features for Esquire, GQ, The Washington Post Magazine, and New York Magazine.

The Unrelenting Optimism of Jamie Raskin

Arnold's Secret to Lasting Influence

The Good News About Cancer

Teaching Under Fire