PART I.

SUNRISE

WALTER CHUPEK IS ready to die. He has been ready to die for months. He breathes as if a plastic bag has been pulled over his head, and each day it clings tighter. Last night, he couldn’t cook dinner. Today, he feels like he’s being stabbed. He tells his wife, Becky, he’s just going to lie down for a nap, but really he plans to lie down and die.

As he collapses, Chupek asks God to please end his suffering, please just let him die. If God does not see fit to let him die, Chupek prays, then perhaps God can give him a lung, just one lung, to replace the cancerous one, hardened and diseased from years at the dump breathing in that burning green sludge.

Just then, the phone rings in the kitchen.

Nearly three hundred miles away, as Walter Chupek, 65, prays from a bed in Davison, Michigan, a man he will never know has met his own God.

A hospital patient, having decided once that, should he suddenly cease, his organs be divided among the living, has fulfilled his promise. An algorithm, initiated by a computer in Virginia, then scanned hospitals within reach of his body, sorted data—blood types, illness severities, orders from the home hospital—and spat out a name, Walter’s name, which appeared on the screen of a coordinator at the University of Michigan Hospital, Ann Arbor, and was transmitted to the surgery department, then to the front desk of the OR, and then to a kitchen phone beside Becky Chupek. She answers. She calls to Walt.

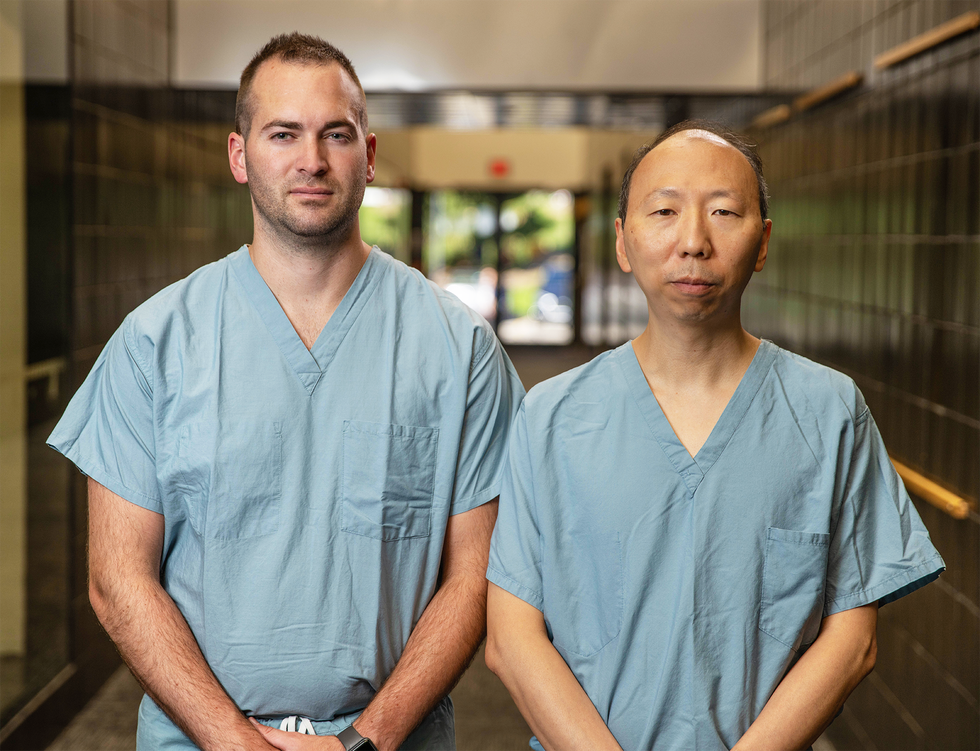

As surgery preparations begin in the OR, a phone number appears now on the pager of Taylor Kantor, M.D., 28, a second-year surgery resident, as he walks down the halls of floor 4C. He dials the number, crosses a bridge to the Cardiovascular Center, and steps outside.

It’s a sunny November morning, the time of year when the biting air portends another brutal Midwest winter. Kantor heads to the ambulance bay where he greets his attending surgeon, Jules Lin, M.D., 48. The pupil and mentor drive to an airstrip just outside Ann Arbor. A plane is waiting.

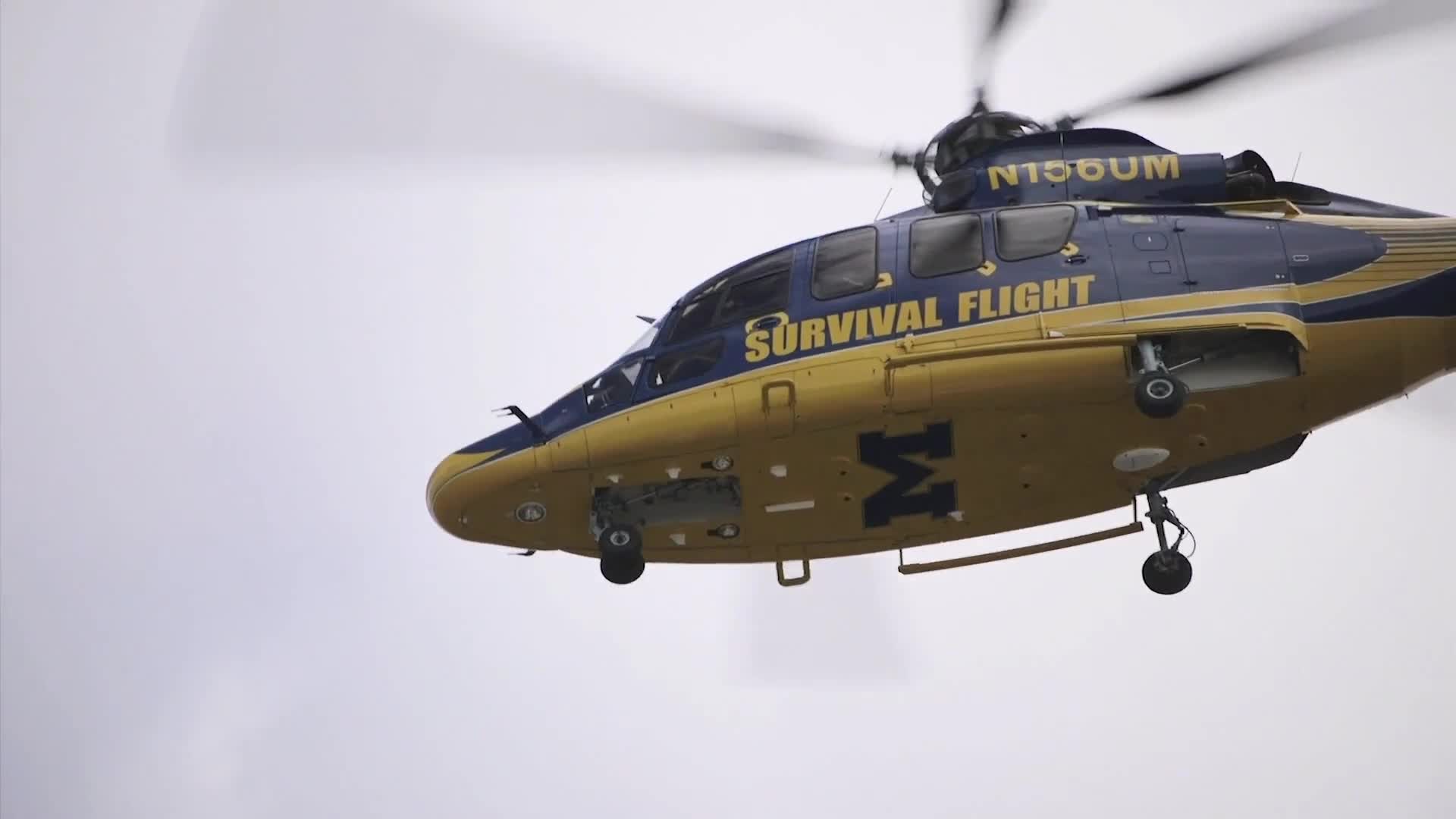

As nurses prepare Chupek for surgery, the jet whirs and speeds down the airstrip, bound 250 miles for a lung, for an answer to a prayer. Along the plane, 14 yellow letters catch the sun: SURVIVAL FLIGHT.

LIVINGSTON COUNTY AIRPORT—0630 HOURS

JEFF THOMAS, R.N., 49, arrives at work wearing his flight suit. He loves wearing his flight suit—in the car in the morning, during the 12 hours of his shift, through the halls of the hospital, in front of wide-eyed kids. There’s a joke some dispatchers tell: How many flight nurses does it take to change a light bulb? The punchline: Ten. One to unscrew it. Nine to sign autographs.

Thomas knows the joke, and he does not care. In the ’80s, when he was training to be a nurse, flight nursing—medicine practiced on helicopters and not unlike practicing on a military transport—seemed like rock stardom to him, too. At the time, few flight teams had the maverick reputation of Michigan’s Survival Flight, founded in 1983, one of the first air-medicine programs in the country and still perhaps the most elite. Thomas heard one story of a Michigan nurse who, upon landing with a patient at the helipad, performed an emergency cricothyrotomy—puncturing the patient’s throat to insert a breathing tube—with a pocketknife.

Unlike other flight programs that deal mostly with local site calls—car accidents and broken bones—Survival Flight focuses on critical-care patients, those facing life-threatening conditions. Serving one of the region’s top medical centers, it represents the only lifeline for many admitted to smaller, remote hospitals. Its aircraft range also gives a growing number of patients waiting for organ transplants a shot at life. Seventeen people die each day waiting for an organ.

Because of these duties, flight nurse qualifications at Michigan are steep: ten years of experience, preferably in ERs and ICUs. Michigan flight nursing also requires surgical tasks that even ER nurses rarely perform, like intubations, neck incisions, and IV placements through the bone. There are 22 flight-nurse positions at Survival Flight, and the turnover rate is not high. No one leaves.

Thomas makes his way across the Rotor-Wing Transport at Livingston County Airport, Survival Flight’s second base, 35 miles from the home hospital at Ann Arbor. The hangar houses one of the unit’s three helicopters, which they use to quickly transport critical patients from distant hospitals to Ann Arbor—helipad to helipad. Also parked here is the unit’s fixed-wing Learjet, used for longer flights. It is currently gone, taking the procurement team, a rotating group of surgeons—today Lin and Kantor—to a lung. They sometimes fly as far as Utah.

Thomas checks his safety status over the dispatch line—how many hours of sleep he got, how fatigued he feels. He’s a 2 out of 10, meaning okay. He slams a Diet Pepsi. Most flight nurses run on adrenaline, caffeine, and sucrose—coffee at all hours, Clif Bars stuffed in various folds and pockets, emergency M&Ms in case a last-minute call turns a 12-hour shift into 24.

This morning, Thomas is paired with Lori Jacobs, R.N., 58, another Survival Flight veteran, with the program since 2002. She emerges from the supply room.

When they started about 16 years ago, Jacobs and Thomas hated flying together. Both chose nursing over the military, both are veterans of other flight programs, both are perfectionists, both are 80-hour-week workaholics, and both get grouchy when they’re not getting overtime. Jacobs took Thomas for an arrogant jerk.

In 2007, Jacobs was working when a Survival Flight jet carrying a crew of six signaled an emergency midair. Thomas was watching his son’s soccer game when he got the call. The jet, transporting a pair of lungs, was unable to land. It crashed into Lake Michigan. Everyone on board was killed, including one of Jacobs’s best friends. Jacobs and Thomas remember that afternoon. The phone calls to the families. The news crews lining the highway. The funerals. They both flew the next day.

The tone sounds, a flat, blaring noise that echoes through the hangar and signals a call: A patient, somewhere in Michigan or Ohio or Indiana or elsewhere, is critical. Without words or eye contact, Jacobs and Thomas begin gathering supplies.

Jacobs made a promise in 2007, after her kids saw her in tears watching news coverage of the crash: She will never leave the house angry, and she will never say, “Bye.” It’s always kisses and “See you later.”

You never know what could happen.

THE JET—0930

THE SURVIVAL FLIGHT jet soars 41,000 feet over an autumn patchwork of browns and yellows and dying greens. Aboard, flying to retrieve the lung that must go inside Walter Chupek by sundown, sit Lin and Kantor.

Lin, the surgical director of the hospital’s Lung Transplant Program and himself the son of a surgeon, is a stolid man. Today, he is the mentor to Kantor, the smiling, outgoing second-year resident.

In med school, Kantor was told to pursue anything other than surgery. He refused. At age ten, he had watched a surgeon like Lin leave the operating room where his grandfather—his father figure after his parents’ divorce—received a bypass. “He would’ve died had we not intervened,” the surgeon had told Kantor and his mother in the hall. It was the surgeon’s poise and swagger in front of death that struck the boy. He wanted that, whatever that was.

Lin quizzes Kantor now about the steps for the dissection. Organs don’t always look the way they do in textbooks when you open the patient. Kantor will have to learn to operate by touch and intuition, feeling the organ, knowing by its weight and composition how to operate.

As the pair pass over distant farm fields, Walter Chupek is wheeled into surgery. He will be prepped and put to sleep and his chest will be opened while, hundreds of miles away, Lin and Kantor reach into the chest cavity of the donor. The operations will occur simultaneously. By the time Survival Flight returns with the new lung, Chupek’s cancerous lung will already be exposed and ready for removal.

He has waited a long time for this moment. It was ten years ago when his doctor first noticed the spot on his lung. He met Becky around then. The diagnosis didn’t stop her. They had their first date at a Big Boy outside Flint. She married him a year later.

He said goodbye to her earlier, outside the hospital, knowing he may never see her again.

DONOR HOSPITAL—1100

THE HARVEST begins with a speech, written by the donor’s family and read by a hospital representative. It recounts the life of the patient—who is laid out before the surgeons, his face uncovered, his chest illuminated with white surgical lamps, like spotlights. The speech tells of who he was and who loved him and what he meant to this world. The room goes quiet. The surgeons, standing, their heads bowed in silence, lift their gaze, approach the table, and begin cutting.

Kantor makes the first incision in the chest. He slices using electrocautery through the skin and tissue and down to the bone. The smell of cleaning agents permeating the OR turns, for Kantor, to that of burning flesh. Lin stands across from him, holding back the tissue with forceps, looking for hesitation, a moment when he might need to walk Kantor through the next cut.

It is not an ideal surgery environment. The Michigan team often visits hospitals for the first time. They operate in foreign rooms with staff unfamiliar with their procedures. To make things more complicated, Lin and Kantor aren’t the only team on site today. Surgeons from several other hospitals gather around the operating table, waiting to harvest the heart and the liver and maybe the pancreas, too. Nearly 20 people fill the operating room, five times the number for most standard operations.

The surgeons must work together. After the initial incision, there is an order: The heart usually goes first, then the lungs, then the liver and kidneys, and then what’s left.

Kantor and Lin cut open the sternum with a saw, using a retractor to pry the bone and access the chest cavity. Kantor makes an incision in the pericardium, exposing the heart. It is still beating. Though the patient is brain-dead, the heart still beats to keep the organs viable. Once all surgery teams are ready, the heart will be stopped with a clamp and then Lin and Kantor will have six to eight hours to remove the lung and get it back to Ann Arbor.

After med school, Kantor had doubts: Was he cut out for surgery? Could he do this work? A year ago, as a first-year resident on the cardiac-surgery floor, he was called to a patient wearing a wound vac, a kind of bag that decreases air pressure on exposed tissue. He was told there was some blood in the vac. When the man stood up, a liter of blood spilled out and splashed across the floor. Kantor couldn’t stop the bleeding. He laid the man down, ripped off the bag, and put his hand into the man’s chest, his finger on the spurting ventricle. Could he do this work? Could he handle loss?

He continues to cut now, dissecting around the blood vessels near the heart. He wants to impress Lin, to show he is a capable surgeon. The lung has to be cut perfectly.

Someone is waiting for it.

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN HOSPITAL, ANN ARBOR—1200

AS KANTOR CUTS, Chupek is lifted onto an operating table. He feels serene. He is ready to sleep or to die. He can make out his surgeon, Rishi Reddy, M.D., adjusting the operating lights and calling everyone by name. And then Chupek makes a joke, maybe his last joke on earth. He asks, “Are you ready, Reddy?”

Reddy looks at him and says, with that confidence only surgeons know, “I’ll see you when you wake up.”

THE HELICOPTER—1100

THE TONE sounding through the Survival Flight hangar is sounding for Louis Boggs.

Boggs, 34, had walked into an ER 150 miles north of Ann Arbor with a pain in his side—a pain so tight and stinging it had woken him before dawn. Through dispatch, Survival Flight learns of the diagnosis: Boggs has leukemia.

Thomas and Jacobs grab their helmets, their radios, two 25-pound flight bags—laryngoscope, tracheotomy kit, infusion pumps, etc.—and their container of drugs (fentanyl, morphine, Ativan, Norcuron). Five minutes after the tone, they’re on board, the doors are closed, the commands are given—the gas, the destination, the control numbers—the radio chatter switches over to air-traffic control, the blades begin to whir. Ten minutes after the tone—“Ann Arbor air-traffic control, this is November 1-5-7 Uniform Mike launching”—the rotors drown out all other noise, pilot Kurt Heinrich pulls back on the controls, and the helicopter is up, up, and into the November skies.

The flight to Boggs, to the town of West Branch, will take about an hour. Thomas and Jacobs are silent. They know the stakes: Boggs’s spleen, already enlarged, could rupture at any time, causing him to bleed internally. They have a blood-clotting agent, though there’s not a whole lot you can do for a ruptured spleen in the air.

The flight is routine. Still, Thomas watches the pilot. Four years ago, after someone spotted a wire, Thomas’s helicopter made an aggressive tilt, jerking him toward the door. His mind had gone to his lunch, to puking up his BLT and corn on the cob, and how, if he puked, nurses on the ground wouldn’t be able to intubate him—and he would probably die. He still avoids that road when he drives; he doesn’t want to glimpse the wire.

The near miss prompted Thomas to see the team’s therapist. It was getting harder, he had concluded—the stress he feels, the suffering he sees. He remembers all of them: a man trapped in his semitrailer, bleeding out, losing his mind; a kid who miraculously survived a car accident and regained consciousness months afterward, on Christmas Day, only to have a seizure and drown in the shower years later.

Jacobs came to Michigan for the challenge and adrenaline after hearing about a nurse who performed a roadside C-section, delivering the baby from a woman who had killed herself by driving into a Home Depot. Now the adrenaline just wears her down. When her boys were younger, they rode dirt bikes competitively, and Jacobs had to leave a race once, thinking of so many violent accidents she had worked. She sat in her car and cried. This past summer, there had been several dead on the lake—crashes while jet skiing, her boys’ latest hobby. It hasn’t gotten easier.

It’s a common phenomenon among flight nurses, seeing everywhere—in every dying patient, every cancer diagnosis, every attempted suicide—one’s child, one’s wife, one’s world.

It could happen to us.

WEST BRANCH, MICHIGAN—1140

THE PATIENT IS pink. He looks healthy. He is standing up in his room when Thomas arrives. Most ER patients Thomas meets are ashen and sedated and have a breathing tube down their throat.

For the past half hour, Boggs has been attached to an IV, sitting with his phone and Googling leukemia. His sister, a pediatrician, had given him the news. “You’re gonna be fine,” she’d said. “It’s gonna be all right,” she’d said. But Boggs knew she was lying. She’d had tears streaming down her face.

“Tell me in your words what’s going on,” Thomas says, hoping to read his patient’s mental state. Boggs begins to cry: “I have cancer.”

On board, Thomas and Jacobs are prepared for the worst: that Boggs’s spleen, now almost three times its normal size, could rupture and cause him to bleed out in flight.

They give him a headset so they can talk with him, ask him about his kids, his job, anything. Every patient they pick up is experiencing the worst day of their life. “We inherit brokenness,” a fellow flight nurse once told Thomas. “And we get broken by what we do and see . . . . And we bring that brokenness home.”

Thomas wants to comfort Boggs. He remembers his own family’s illness, the dark summer of 2010—telling his three kids on the front porch about their mom’s cancer, shaving Tina’s head before chemo, driving with her to his own place of work, the University of Michigan Hospital, for treatment. He hated the hospital. He hated the cancer. The couple were supposed to adopt a son that summer. The cancer took that from them.

What might it take from Boggs?

DONOR HOSPITAL—1200

THE HEART TEAM has already removed the most vital organ. Next, Kantor must dissect the lungs. He positions his scissors to make a cut. He waits for Lin to dissent—“don’t make that cut,” “higher,” “a little lower,” “stop.” He adjusts, then he slides the scissors across the tissue, freeing more and more of the lung. He pauses. He repeats. He doesn’t want to cut too close and cause bleeding or, worst of all, make the organ unviable for the recipient.

Don’t fuck this up, he thinks to himself.

He severs the pulmonary ligament attachments. He cuts the posterior pleural attachments. He dissects the trachea away from the esophagus, applying a stapler to it. He moves finally to the pericardium, cutting away these attachments to the now-absent heart.

Together, Kantor and Lin lift the lungs out of the body.

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN HOSPITAL, ANN ARBOR—1245

REDDY BEGINS carving into Chupek. The preparation for transplant could take two hours, and the surgeon doesn’t want the lung waiting around on ice after it comes through his doors. He begins, making an incision in Chupek’s lower chest muscle, opening up the ribs and exposing the lung up to where it connects with the heart. Chupek’s lung looks scarred and shriveled.

His other lung will have to support his breathing while the new one is transplanted. If that other lung, or his heart, isn’t strong enough, Chupek will be in trouble.

MIDLAND, MICHIGAN—1400

THE WORLD HAS gone dark for Shannon Oberloier. She had been cooking mashed potatoes when she heard a pop. Then she got dizzy—like when she rode the spinning strawberries at the fair. Everything went blurry and geometric, and she couldn’t see. The left side of her body shut down; she couldn’t stand. And then she couldn’t talk. When she arrived at the hospital in the town of Midland, doctors began asking questions, scary questions, like how they might carve into her skull and whether she would like to be resuscitated if she died.

Oberloier is terrified.

Louis Boggs remained stable all flight. Thomas and Jacobs had dropped him off in the ER just before the tone sounded for Oberloier. They arrive now over Midland. The earth is still scarred from the flood earlier in the year, when the dam burst. From the air, the land looks drained.

At the hospital, they find Oberloier, 34, lying on the floor in a dark room without monitors. They need to get her to Ann Arbor so she can receive specialized care, perhaps surgery. Her brain, Thomas worries, isn’t getting enough blood, and she may not be able to recover motor functions, memory, speech. Stroke patients are always time bombs: Every minute can mean loss.

Thomas and Jacobs will need to be ready with a breathing tube, extra IVs, and sedatives, the two of them watching for exterior signs like dilating pupils or reflex vomiting.

For the moment, Oberloier seems stable. As she’s wheeled out, Jacobs narrates every move—a bump here, a turn there, a door, the outside.

“I don’t like flying! I drive everywhere!” Oberloier suddenly shouts. She has flown only three times in her life. She cried each time—the entire flight—once while pregnant with her third child.

Thomas reassures her about the flight time, gives her a blanket, tells her to raise her hand if she has questions. She looks like his wife, he thinks, but younger, around the time she was diagnosed with cancer. First Boggs and the leukemia, now Oberloier and three children perhaps losing their mother. Every so often, Thomas has a day like today. He believes these days come for a reason. He believes that God chooses his transports for a reason—to remind him, perhaps. Or to test him. He isn’t sure.

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN HOSPITAL, ANN ARBOR—1500

KANTOR RETURNS to floor 4C, carrying a cooler. The lung spent the hour-long flight in a small cargo area, held in a bag and submerged in several layers of ice water inside the plastic container.

Kantor removes the lung and places it on a table behind the unconscious body of Walter Chupek.

He trims extraneous tissue around the organ for when Reddy will complete the transplant. Kantor has watched the procedure before in this room. He has watched surgeons do—in seconds, seemingly—the impossible.

That day, not long ago, when the man stood and spilled a liter of blood across the floor, Kantor held the man’s heart as the nurses and other staff put in a central line, began giving blood, and wheeled him into an operating room, Kantor still holding pressure on the heart. Before beginning, blood still spurting, the surgeon customarily asked the room if anyone had concerns about the operation. Kantor almost laughed. And then the surgeon grinned and fixed the bleed in seconds. Kantor had held the heart for nearly 45 minutes.

I can do this, he had thought to himself. I am cut out for this work.

Kantor finishes carving the tissue, exhales, and leaves the OR.

THE HELICOPTER—1530

OBERLOIER FIXATES on the sound of the whirring blades.

Thomas watches her blood pressure. He imagines her husband, on the road for work, getting that call, hearing the diagnosis, powerless to help the woman he loves. Oberloier, he learned, homeschools her children, as Thomas’s wife did. Emotions come not in explosions but in waves, pieces of debris that accumulate and build. He remembers when his kids were that age, his wife sick with cancer, him away, working, the kids with Grandma.

God has chosen him to meet Oberloier for a reason.

Oberloier raises her hand. “How long?” she asks.

“Ten minutes,” Thomas replies. She likes the sound of his voice. Its confidence soothes her.

Survival Flight lands in Ann Arbor. The day’s earlier motions repeat: The patient is wheeled into the ER, more nurses take the handoff, Thomas lingers as if unwilling to part, and then the patient is taken away.

The sunlight is dying. The night crew will be arriving soon to relieve Jacobs and Thomas. They fly back to the hangar.

The ride is quiet. Thomas is thinking about dinner—tacos, the family’s favorite. It’s the meal they eat when everyone is together. Sometimes they go months without such meals. Thomas isn’t sure how attentive he can be tonight, if he can ask his kids questions, if he can be the jovial dad—if he can protect them from the brokenness.

When he was 16 and working as an EMT, Thomas watched a grown man break down after his son’s overdose. Thomas hadn’t known how to process that. It took him a long time to understand suffering, how many shapes it takes, how the shapes change and shade people differently, and how knowing his own suffering, he might better talk to his patients, know them, be with them. His wife’s cancer changed all that. The cancer could always return; life is too short. These are the things one lives with and learns.

Jacobs, who was by then flying frequently with Thomas, saw the change during those months, watched their relationship improve, watched Thomas become less stubborn, more open. They exchanged jokes and food—homemade sugar cookies left in lockers; hot tamales cooked for the other’s family.

Thomas walks back across the parking lot still wearing his flight suit. He slams another Diet Pepsi and turns on James Taylor—James Taylor is for the bad days—and drives home through the gathering dark.

PART II.

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN HOSPITAL, ANN ARBOR—1730

WALTER CHUPEK opens his eyes. The hallway is foggy. He is being wheeled somewhere. Conversation fades into focus.

“. . . taking you to your room.”

“. . . we have to sit you up.”

He tries to sit. He realizes he must breathe, and so he tries to breathe. Some lung patients, he heard, wake from surgery and believe they have gone to heaven; miraculously, their breathing is clear.

But when Chupek takes that new-lung breath, he feels only earthly pain. Perhaps he should have died. Perhaps it is all a cruel trick. Perhaps this is hell.

THE HELICOPTER—2200

IT IS HELL, too, a hundred miles away, for Elliot Garnett,* who sucks oxygen out of a tank. He’s taking in about 60 liters every minute. He can’t walk, can’t speak more than five words, can’t do anything without the tank. He needs a miracle, a new lung. He needs to be transported to the university tonight.

Through night-vision goggles, 3,000 feet above, Chad Stoller, R.N., can see spots of glowing white against phosphorous green—a porch light still on, a backyard campfire. Stoller, 34, and his flight partner, Jennifer Rosa, R.N., 48—the night-nurse crew—relieved Thomas and Jacobs just after sunset. They will fly until daybreak. The pair are younger, just eight years of flight-nursing experience combined. There are days Stoller wonders how long he’ll be able to last.

Every June, on the anniversary of the 2007 crash, the university gives a presentation—on flight, on safety, on emotional stress. One year, Stoller learned about metaphorical armor, how flight nurses bear trauma, how it takes just one arrow to penetrate the plates, and how it’s not a matter of if a flight nurse will reach their breaking point but when. It’s a conversation he has had with Thomas. He looks up to Thomas, ever since their first call together—a truck driver trapped in a maze of metal and bleeding out on the roadside. Since then, the two occasionally grab a beer together. Stoller hasn’t yet seen the team’s therapist. For now, beers with Thomas are enough.

Down below somewhere, Thomas is nodding off to a cooking show. He had come home dejected. He’d showered and sat down to tacos and guilt—the family was finally together, but Thomas was gone. When the conversation came his way, he had simply picked up his head and said, “Today was a bad day.” The conversation went on without him.

He sits on the couch beside his daughter and his wife. Tina Thomas has been cancer-free for 11 years. Even when she was sick, she still homeschooled the children, still lived her life as if the illness weren’t threatening to destroy the family. Thomas is in awe of her strength. The brokenness pays for something, he likes to remind himself. And he does love the job. But sometimes, like today, it is crushing. He falls asleep. The cooking show continues to play.

Up in the dark skies over Lansing, Stoller scans for antennas. He is wearing his helmet, an N95 mask, gloves, and a blue plastic gown—an annoying, finicky layer, like a garbage bag—over surgical scrubs. It clings to his skin.

He sent a text to his wife shortly before takeoff, telling her of the call—“Hi Beautiful. ICU flight. Love you.”—but not the details. She has since texted and gone to bed. He will send an email when he returns. These past few years saw a series of air-medicine crashes—one in Wisconsin killing three, one in Ohio killing three, and one in Minnesota killing two. At first Stoller texted after every flight, but his wife would wake late with anxiety and check her phone. Now he emails.

Rosa started flying for the unit in February of this year. Covid was her rookie season—streams of patients brought from Detroit by ambulance to Ann Arbor, early mornings after work stripping down in her garage, like a hazmat zone, hundreds of showers. She remembers the desperation and fear among the ER nurses, the resource scarcity in smaller hospitals, plastic sheets duct-taped between beds, shower curtains worn as gowns, painting respirators used as masks.

“What’s our plan for DFO?” Rosa asks Stoller—DFO for “done fell out,” when a patient faints or, in this case, if oxygen drops and they need to intubate. They decide beforehand who will do it. “As the senior flight nurse, I think you should do this one,” Rosa teases Stoller over the radio. Stoller smiles wide and laughs. “Fine,” he concedes, though he hopes the patient won’t need intubating. Once intubated, some patients are never able to breathe on their own again.

Intubation could mean a death sentence.

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN HOSPITAL, ANN ARBOR—1830

"WALTER ,YOU need to slow your breathing,” the nurse says. Chupek’s body is rebelling against the foreign object, the organ that traveled hundreds of miles that day to be put inside him. Why would God answer his prayer with such pain? Chupek tries again.

His stepchildren are calling and texting—How did it go? How are you? He left the phone with Becky.

He is not allowed to see her yet.

Chupek is learning how to do it again—to breathe. To inhale . . . exhale. Inhale . . .

THE HELICOPTER—2300

GARNETT'S EYES are wide. His face is sallow. He is panting as if he has just finished a long run.

Stoller and Rosa had brought in 660-liter canisters from the helicopter, an overcompensation, in case of exigencies—a stalled elevator, a security guard getting lost leading them out of the hospital. They’ve all happened before.

“We’re going to be transporting you, and something could happen,” Rosa explains. “We just need to know: Do you want everything done?”

Garnett begins to cry. Between gulps of oxygen, he finally says, “Yes. I want to live.”

Though she is relatively new to Survival Flight, Rosa spent more than two decades in pediatric critical care. She learned there how to compartmentalize—a sick teenage boy is not her teenage boy. The older father before her is not her father. It’s unhealthy, Rosa thinks, for a nurse to see her family in her patients. You can’t let them affect you.

Rosa and Stoller switch Garnett’s oxygen over to their tanks, bundle him in blankets, and take off down the hallway and then out into the night. Rosa’s goggles fog. The cold wind whips Stoller’s sweat-slicked plastic gown, blowing it everywhere as he and Rosa load Garnett into the helicopter.

Some hospitals keep critical patients for more than a week before calling Survival Flight, and Stoller wonders if Garnett has stayed too long. Several times, Stoller has arrived at a bedside where nurses whisper frustrations to him—“I wished they’d listened”; “they should have called you two days ago.” He looks at Garnett and knows Garnett will likely die.

Stoller remembers a girl who was pinned in a car after a highway accident. He intubated her, brought her back from the brink, flew her to the hospital. She died soon after. Before she passed, there was enough time for family to say goodbye. Somehow, that goodbye made Stoller feel better.

After an hour-long flight, Garnett is dropped off at the ER. Stoller and Rosa fly back to the hangar. Everything is scrubbed and cleaned and disinfected.

Stoller teases his partner: “You were so mean—you made the patient cry!” Rosa laughs. Stoller feels like a little brother sometimes. He handles the stress well. If it affects him, if the arrows pierce his heart, he doesn’t show it. There are arrows that have penetrated his armor—dying kids and roadside carnage—but the arrow tonight has not struck. More will come tomorrow.

Stoller can finally strip off his scrubs. He pulls the soaking plastic from his body. He sends his wife an email: “Back safe. Love you.”

SUNRISE

ON THE NORTHEAST corner of the University of Michigan campus, up the hill from a Survival Flight helipad and just outside the hospital’s eastern entrance, there is a monument: an oblong wall standing ten feet tall and curving 50 feet around, it contains 600 metallic rotors, which fit into an orderly grid and sway slightly in the breeze. The monument was built in 2009, two years after the Survival Flight crash that killed six crew members—David Ashburn, Richard Chenault II, Dennis Hoyes, Rick LaPensee, Bill Serra, and Martin Spoor.

On this November morning, as the sun rises and the curtain of light climbs over the horizon and then the Huron River and then the helicopters down the hill, the statue’s rotors gleam, and the light falls on the hospital and enters the rooms of its patients.

Walter Chupek wakes. He had a restless sleep after last night’s surgery, after he took his first breaths on his new lung. He didn’t know if he’d wake up today.

But as the sun rises, Chupek is ready for another breath. He takes it, slowly this time, deeper this time. He inhales . . . exhales. It isn’t perfect yet. But it’s getting better.

At the Survival Flight hangar, the night shift has finished charting and has organized the helicopter for the next shift—Thomas and Jacobs, who will arrive 30 minutes early in case the tone sounds on the 12th hour. All nurses arrive early for their team.

In Brighton, Taylor Kantor’s dog is running around his bedside as he sleeps in for the first time in what feels like forever, his 80-hour surgical week behind him.

Lori Jacobs crosses the border from her home in Indiana, on the road to Starbucks and her daily order—peppermint latte, honey-citrus tea, peach green-tea lemonade.

And in Howell, Jeff Thomas enters the kitchen to the smell of onions and eggs frying. It is the breakfast his grandma used to make and the one Tina makes now almost every day. It is his comfort food. He eats, rejuvenated. He says goodbye to Tina and the kids. He puts on his flight suit. He grabs his Diet Pepsi. He bounds out the door.